- Home

- Archive -Mar 2010

- A Capital Idea

A Capital Idea

- In :

- Personal Growth

March 2010

By Dipankar Das

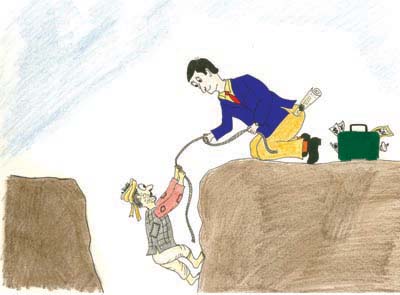

Should corporates not be responsible for the citizens’ well-being? The author delves into the question that launched a thousand initiatives

|

The uber guru of monetary economics, Milton Friedman, had famously quipped, “The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits.” Friedman had a penchant for controversy, and his observation is often a red flag for those who campaign for business to be more responsible. But the good news is that there is a holistic change taking place in the boardrooms.

For starters, the businesses have often pushed the limits of human endeavour in pursuit of profits. Henry Ford, through a series of innovations, made the automobile available at a price at which the American middle class could afford a car. Closer home, the e-choupal initiative, launched by ITC has empowered thousands of farmers across the country to seek better rates for their crops, which they could not some time ago. It has triggered a virtuous circle of higher productivity, higher incomes, and higher capacity, while benefiting the company in multiple ways. Similarly, Project Drishti launched by Reliance Industries, has restored the sight of thousands of individuals. Thousands of inventions and discoveries have been prompted by the impulse to make profits, be they cancer drugs or cellular technology, the list goes on.

The idea that organisations are responsible for more than profits is really an old one. In the eighteenth century, factories built houses for their workers, in the belief that a well-housed employee is a more productive employee, or in today’s context, a more motivated employee. In India, the Tata group adopted Jamshedpur as its own and transformed it into a model town. Jamshedji Tata pursued all channels to improve the civic conditions in the city. The Aditya Birla Group and Indian Oil have been involved in helping disadvantaged sections of society since their inception.

The global perspective

Globally, the debate about social responsibility has been too complex to be paraphrased. But for all practical purposes, it can be distilled into three strands.

The environment: This has evolved from the simple demand that companies stop belching smoke from their chimneys to getting their carbon footprints in order. They have to curtail their appetite for natural resources – bits of Brazilian rainforest or skins of rare animals. The popular mood has taken such a bleak look at such behaviours that companies are now forced to boast, “Make no mistake, all our furs are fake.”

Exploitation: Globalisation has meant organisations are criss-crossing across the globe with easy access to markets and the labour pool of less developed countries. There is a feeling that globalisation has enhanced the power of multinationals to exploit the poor and the power of trade unions meant to protect the workers has diminished.

Bribery and corruption: The Enron phenomenon has laid bare the unhealthy working of many organisations. Business with integrity and ethics has since then become a byword in large organisations. Tainted money no doubt enters business, but the movement for clean corporate governance too has never been stronger.

Friedman’s wisdom

Since the chief mode of poverty reduction has remained the trickle-sdown mode in the country, the mere establishment of a business creates opportunity for the people starved for opportunities. So even if one were to stick to Milton Friedman’s observation that businesses should restrict themselves to making profits; it helps in an opportunity-starved country such as India. For example, the nascent BPO industry employs about three lakh employees. And according to a conservative estimate each BPO job imported from outside, results in generating five support jobs in security, housekeeping, and other functions.

CSR in India

Thankfully, it is not restricted to just a trickle down, but is being pursued actively by organisations, large and small. Corporate social responsibility is even more relevant in a country such as India, given the levels of poverty and lack of infrastructure in the country. Indeed, it is increasingly becoming a part of corporate strategy. These programmes, in many cases, are based on a clearly defined social philosophy, or are closely aligned with the companies’ business expertise. Employees become the backbone of these initiatives and volunteer their time, and contribute their skills, to implement them. CSR programmes could range from overall development of a community, to supporting specific causes like education, environment, and health care.

|

For example, organisations such as Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited, Maruti Suzuki India Limited, and Hindustan Unilever Limited, adopt villages, where they focus on holistic development. They provide better medical and sanitation facilities, build schools and houses, and help the villagers become self-reliant by teaching them vocational and business skills. On the other hand, GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals’ CSR programmes focus primarily on healthy living. They work directly in select villages, providing free health check-ups and medicines, helping NGOs in the health sector, and supporting the underprivileged.

For example, SAP India in partnership with Hope Foundation, an NGO that works for the betterment of the poor and the needy throughout India, has been working on short and long-term rebuilding initiatives for the tsunami victims. Together, they also started The SAP Labs Center of HOPE in Bangalore, a home for street children, where they provide food, clothing, shelter, medical care and education. Businesses have some of the best brains in the country as also the expertise to bring about positive changes. The energy, vision and focus that is used to generate profits in a narrow context, when deployed in the larger social context, particularly in partnership with NGOs and the government, has huge potential to change the country.

Win-win

The most important win for CSR, however, is the emerging convergence between profits and social responsibility. There is a gradual realisation that there are significant profits to be made at the bottom of the pyramid. More and more companies are innovating by making products available at prices, which the poor can afford, and benefit from. Business organisations are also realising they cannot be divorced from the ecosystem of the economy, which encompasses their workers and consumers. Added to this, the increasing consensus around environmental and social practices has not left organisations with a choice. As Niall Fitzgerald, former CEO of Unilever observed, “Corporate social responsibility is a hard-nosed business decision. Not because it is a nice thing to do, nor because people are forcing us, but because it is good for our business.” Such convergence is the seed of a more holistic world, united in its purpose.

Dipankar Das started his career at Life Positive. He now works as a Training and Development specialist.

To read more such articles on personal growth, inspirations and positivity, subscribe to our digital magazine at subscribe here

Life Positive follows a stringent review publishing mechanism. Every review received undergoes -

- 1. A mobile number and email ID verification check

- 2. Analysis by our seeker happiness team to double check for authenticity

- 3. Cross-checking, if required, by speaking to the seeker posting the review

Only after we're satisfied about the authenticity of a review is it allowed to go live on our website

Our award winning customer care team is available from 9 a.m to 9 p.m everyday

The Life Positive seal of trust implies:-

-

Standards guarantee:

All our healers and therapists undergo training and/or certification from authorized bodies before becoming professionals. They have a minimum professional experience of one year

-

Genuineness guarantee:

All our healers and therapists are genuinely passionate about doing service. They do their very best to help seekers (patients) live better lives.

-

Payment security:

All payments made to our healers are secure up to the point wherein if any session is paid for, it will be honoured dutifully and delivered promptly

-

Anonymity guarantee:

Every seekers (patients) details will always remain 100% confidential and will never be disclosed