- Home

- Archive -June 2020

- A TSUNAMI IN MY. . .

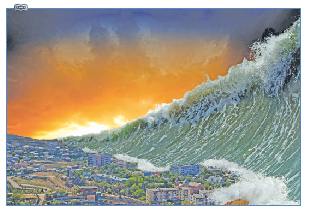

A TSUNAMI IN MY HEART

- In :

- Braveheart June 2020

While carrying out relief work in the wake of the tsunami, Raja Karthikeya encounters a unique man who epitomised the philosophy of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam—the whole world is a family

When the tsunami came on 26 December 2004, I was barely touched. I worked for a large software company in Bangalore, and the only disaster I knew of was not meeting my quarterly revenue targets. The day after the tsunami, I was having coffee with a colleague in the company cafeteria, when the conversation turned to the disaster which had killed 200,000 people across Asia in a span of seconds. What a tragedy, I remarked. He took a deep puff of his cigarette and sighed, “Yeah, but what can we do?” Something about that remark made me sit up. I was 25, physically fit, had an MBA from a top business school, and was a fast-rising professional in an Indian multinational. My ambition kept pace with my confidence, and I was earning enough to say that I lacked nothing. And yet, I did not seem to have an answer to this simple question: “What can we do?”

Let’s do it

Three days later, I called up the Indian Air Force’s missing persons helpline and convinced officials to let me fly on a cargo plane to Car Nicobar, one of the southernmost islands in the Andaman and Nicobar archipelago, and the worst hit by the tsunami. A quarter of the island’s population, nearly 5,000 people, had been wiped out by the tsunami. The rest had fled into the jungles in the interior of the island. I volunteered to work with the army and paramilitary troops scouting trails in the jungle, taking count of the survivors and delivering relief supplies.

Second thoughts

But after 10 days of relentless work in the jungle and sleeping in the open on the hard concrete of a runway in the island’s airbase with my backpack for a pillow, my self-confidence started wearing down. My clothes were stained with sweat and grime, and all I had left to wear was a ‘camou’ borrowed from the military. With seawater and debris contaminating the wells, fresh water was so precious that it was pointless to think of a real shower. Fatigue began to hit me, as well as doubt. Why was I here? I even wondered if my decision to be on this remote island in a corner of the Indian ocean had just been an act of ego. In the nights, when I trekked alongside the soldiers under the clear tropical sky, I’d occasionally gaze up at the stars and wonder if I really knew what I was doing. I was far from my family in Hyderabad, and with all the cell towers brought down by the disaster, I had no means of reaching them. I was absent without leave from work and may not even have a job left when I got back to Bangalore. I had no idea when and how I’d get back from the island to Bangalore either. I went about the relief work one day after another, in increasing silence.

Motivating the youth

And then one morning, I met Philip. The day before, an army officer, Lt Col Bisht, and I had managed to reach the village of Sawai in a far corner of the island by helicopter. The village of 1,700 people had been totally cut off from the rest of the island by the tsunami. All roads leading to the village had been swallowed by the sea, and the only way out of the village was through dense, tropical jungle, without any motorable road or even a clear walking trail. We needed to urgently connect the village to the outside world to allow relief supplies in. With much of the village destroyed, the villagers were living in small huddles in the jungle, as far from the treacherous sea as possible, surviving on a tasteless, fibrous fruit called kewry that they plucked from the bush. Living under the trees was miserable when it rained at night, and the threat of disease from dead and rotting livestock was increasing. I went to the tribal chiefs who oversaw each huddle and persuaded them to send some youth with me to carve out a trail. With luck and persistence, I was able to mobilise a large group of tribal youth from across Sawai to hack a trail through the jungle to the nearby village of T-top, from where the highway could be accessed.

Despondency sets in

That morning, I had organised some 200 young men to hack the trail and was somewhat confident that we would be able to hack through the five km of jungle in a day or so. But after two hours, I looked back and took count and was shocked to see that there were barely 10 left. Tired and hungry, most of the men had returned to their settlements. My heart sank. I felt angry because we still had miles of jungle to cut through. I became furious when I noticed that even these remaining 10 started turning back. I stopped them. They said they would come back in a while. I knew they weren’t going to. They were too tired and simply seemed not invested in the trail.

I calmed myself and tried to reason with them. I told them this trail was for the future of the village, for every one of their children who needed to go to school in the neighbouring village, as their own school had been destroyed by the tsunami. This trail would become a road that was their own. They could not give up on it now. We had to hack our way through to T-top. This was Sawai’s lifeline—its only connection to the rest of the world. But no matter how much I tried, the men would not budge. They were exhausted and weak from weeks of near-starvation, and I felt I wasn’t getting through.

My own fatigue, after two weeks of relentless relief work with little sleep and constant physical strain, started to surface. Sweat dripped down my forehead, and my eyes were burning. I had water blisters on the soles of my feet, and every step I took made me wince. As I firmly held a machete I had found to cut through the bushes, my shoulders ached, and sharp bursts of pain shot from my shoulder into my back.

I now yelled at the young men asking them to stop. I said that if they weren’t going to come, I was going to hack the trail myself. I asked if there was even one who would join me. Without waiting for a reply, I took my machete and started hacking the vines and trees around me.

One man, big difference

Suddenly, I noticed that a short young man stepped up and joined me. Together, we left the group and started slicing through the undergrowth. Minutes later, to my absolute surprise, I observed that one after another, all the men in the group had walked up and joined us. I was taken aback. What had changed, I wondered. This was by no means a product of my persuasion. This was a miracle.

I wanted to know who this young man was, for it was certainly he that was the prime mover, the catalyst for the change. His name was Philip. He was 25, the same age as me. But there the similarity ended.

Philip had lost his wife and eldest child just two weeks earlier in the tsunami. His most loved ones were gone, lost to the sea in a matter of seconds, along with everything he had ever owned. His younger son had survived but was now burning up with a potentially fatal fever.

I swallowed hard. I did not know what to say. I had never experienced such personal agony, but after seeing first-hand the nuclear holocaust-like destruction wrought by the tsunami, I could just about imagine a bit of all that had happened. My eyes watered on thinking of what Philip must have gone through in those moments when he had helplessly watched his wife and child carried away by the sea. His face strangely seemed to be set in stone, and it felt as if he was narrating someone else’s life, not his own. But deep in his eyes, I could see a pain that I cannot begin to describe. Even as my hands kept slashing at the trees, my mind was racing. I fervently wished I could say or do something to help Philip. I wanted to help him. I needed to help him.

I urged him to leave us and run down the trail to the next village to get medicine for his surviving son. “Lt. Col. Bisht is in that village already. Tell him that I sent you, and get medicines for your son.”

Philip shook his head. He wasn’t leaving. He was going to work on the trail.

I didn’t understand him.

“What about your family, Philip?” I asked exasperatedly, thinking it was only appropriate to still refer to them in the plural.

His next words hit me like a tidal wave.

“Saara gaon mera parivaar hai, Saab.” The entire village is my family.

I replayed the words in my mind several times. What was he saying? How is it possible, I wondered, to view our entire community, our entire society, our entire country or, perhaps, all people as being the same as our family? How is it even conceivable to care for all people with the same passion as we would for our loved ones?

And then it dawned on me. Philip was not saying that his village was like his family. He was saying that to him, family meant his entire village.

Epiphany

Something changed within me. I suddenly felt as if my work had found new meaning. Suddenly, sales targets and software did not matter as much. After weeks of seeing nothing but pathos—from bloated corpses to uprooted houses and floating toys—finally, a note of bliss made its way into my heart and brought a soft smile to my lips.

Philip moved ahead of me, hacking through the foliage, unaware of the transformation his words had brought within me. I reflected on it. This man on a remote island in the Indian ocean had neither wealth nor formal education. He had no possessions left anymore after the worst natural disaster in human history and had lost everything he had ever bought and owned. And yet, he had stepped up when his village was in need because he had looked beyond ties of blood and identity.

The death of his young wife and child—horrors which would have destroyed any other man—did not diminish him. He prized the future of all the children of the village as much as the survival of his remaining son. The entire village was his family.

Sunshine began to stream through the leaves overhead, suggesting that after all our effort, a trail had finally begun to clear. I thanked Philip silently. This young man wasn’t just cutting a trail through a jungle, he was showing me a path for life.

Shortly after this experience, Raja Karthikeya quit his job and became a humanitarian aid worker. He has since served in United Nations peace operations in Afghanistan and Iraq.

To read more such articles on personal growth, inspirations and positivity, subscribe to our digital magazine at subscribe here

Life Positive follows a stringent review publishing mechanism. Every review received undergoes -

- 1. A mobile number and email ID verification check

- 2. Analysis by our seeker happiness team to double check for authenticity

- 3. Cross-checking, if required, by speaking to the seeker posting the review

Only after we're satisfied about the authenticity of a review is it allowed to go live on our website

Our award winning customer care team is available from 9 a.m to 9 p.m everyday

The Life Positive seal of trust implies:-

-

Standards guarantee:

All our healers and therapists undergo training and/or certification from authorized bodies before becoming professionals. They have a minimum professional experience of one year

-

Genuineness guarantee:

All our healers and therapists are genuinely passionate about doing service. They do their very best to help seekers (patients) live better lives.

-

Payment security:

All payments made to our healers are secure up to the point wherein if any session is paid for, it will be honoured dutifully and delivered promptly

-

Anonymity guarantee:

Every seekers (patients) details will always remain 100% confidential and will never be disclosed