- Home

- Archive -Apr 2009

- The Dargah Of N. . .

The Dargah Of Nizamuddin Auliya

- In :

- Personal Growth

April 2009

By Arun Ganpathy

The dargah of the great Sufi saint, Nizamuddin Auliya, is a vibrant repository of his love and compassion.

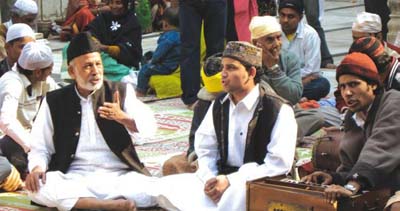

The qawwals commune with God The qawwals commune with God |

There is a heady whiff of spiced seekh kebabs as you walk along the winding alley. It makes you want to stop and take a few sniffs. You do. But the drifts of smoke burn your eyes and you move ahead. Presently other smells and sights take over – fresh flower petals, burning incense and technicolour chaadars announcing the entrance to one of India’s greatest Sufi shrines – the dargah of Nizamuddin Auliya in Delhi.

Hazrat Khwaja Nizamuddin Auliya was born in 1238, in Badayun, Uttar Pradesh (east of Delhi). At the young age of five, he lost his father and came to Delhi with his mother, Bibi Zuleka. Not much is known of his early life except that it was spent in assiduous study. As a young man, he was thoroughly familiar with the Koran and the Hadith.

Then, one day, something happened.

“I was reading a paean to Muhammad when a singer named Abu Bakr who had visited Multan and Ajodhan came to my teacher and began to narrate experiences of his journey. ‘He told me he had proceeded from Multan to Ajodhan and seen a mighty king there – in short, when the praises of Sheikh Maulana Fariduddin fell on my ears, I developed a sudden and intense love for him.”

Nizamuddin decided to travel to Ajodhan to meet the sheikh. Much like what happened to Rumi when he met Shamsuddin Tabrizi, the course of Nizamuddin’s life changed, after this meeting. From that moment on, he swore allegiance to Sheikh Farid and almost abandoned scholarship, choosing instead to rely on mystical insight and the practice of austerities. He visited Ajodhan each year to spend the month of Ramadan an in the presence of Sheikh Farid, and on his third visit, he was appointed the sheikh’s successor.

Shortly after that when Nizamuddin returned to Delhi, he received news that Baba Farid had expired.

Nizamuddin continued to live at various places in Delhi, before finally settling down in Ghiyaspur, a neighbourhood on the outskirts of Delhi (in his time).

The Siyar-al-auliya, a biography of saints of the Sultanate, recounts Nizamuddin’s daily routine, especially his practice of fasting.

“Nizamuddin maintained a strict personal regimen. At the time of iftar he would eat very little; when food was brought in early morning he would usually refuse it, fasting continuously. A servant would plead with him to eat. ‘I think of the many poor people and beggars suffering hunger and deprivation, huddled around the mosques and sleeping in the streets of the city. How can this food go down my throat?’”

Nizamuddin’s answer was a reflection of the lifelong compassion towards the poor and the non-elite who continue to throng his tomb even to this day.

Nizamuddin preached a gentler doctrine of reconciliation Nizamuddin preached a gentler doctrine of reconciliationand his love and humanitarianism extended to all |

As I walk around making my notes, I notice there is a complete absence of well-to-do or camera-toting pilgrims. Wild-haired fakirs and famished beggars shuffle across the cool white marble courtyard, pestering pilgrims for alms. Professional beggars have made this their home. Meanwhile, the few pilgrims who are here, sit in a neat U-shape under a shamiana in front of the main tomb, the women to one side and the men to the other. At the U-end is four qawwals – they start a tune praising the saint as a lover of the poor.

‘Garibo ki Nawaz .. o Garibo ki Nawaz’, sang the lead singer, throwing his hands out in the direction of the tomb and rolling his head in a frenzy. The tabla kept up with its deep heart-wrenching boom and in a few moments, some of the pilgrims had joined the qawwals, clapping, and singing. Their voices, though discordant, had a captivating effect on the rest of the audience.

Sensing the mood the qawwals sang faster. The audience broke into a sweat and a dervish went around fanning them with a shield-shaped cloth fan. The qawwals raised their voices and sang even faster, driving to a climax. Such was the effect of the music that soon the whole audience was ecstatic and the place transformed into a mass of swaying white kufi caps. Enthralled as I was, I knew that what I had seen reflected the saint’s love of music and poetry, which often moved him to ecstatic states.

This ecstatic behavior frequently brought him into conflict with the Sultan as it was against orthodox Islam. Once, when Sultan Baban called Nizamuddin to explain why his followers indulged in music and dancing (inside the mosque) the dervish replied:

“When Allah’s grace enters one person it manifests that person to sing and dance with joy. If this is a manifestation of being possessed by Allah I say, Ameen.”

The saint’s miraculous power turned water into the oil The saint’s miraculous power turned water into the oil |

Nizamuddin escaped on this occasion, but it would not be the last time he would run into trouble. When Giyasuddin announced plans for the building of a new capital at Tugluqabad, he needed all the workmen he could find including those who were working on the saint’s project of building a tank to collect rainwater near his khankah in Ghiyaspur. The sultan’s order took preference, but the workmen returned at night to continue building the tank by the light of the oil lamps. This infuriated Giyasuddin who put an end to the sale of oil.

The story goes that Nizamuddin then ordered the workers to use water from the tank instead and it worked equally well.

The baoli they dug is the first thing you see as you enter the shrine.

Biobi, the khitmatgar, let me in, unlocking the small grill door. Inside was a large square well surrounded by the high walls of the basti. Set in one of them was a large black urn Diya, which Biobi said was the lamp that the sultan’s workmen had used to work by night. Yes. The saint’s miraculous power turned water into the oil.

“Drink some,” said Biobi, urging me to go down the flagstone steps that led to the water’s edge, “it is healing.” I hesitate as the water is slimy and empty milk sachets and water bottles float on the surface. Bio by continued with her life story. She came here for the first time 40 years ago, weakened by illness. She took a sip of water believing in its miraculous power. She was cured, and ever since that day, she has continued to live here and taken it upon herself to look after the well.

It is incidents like these that Nizamuddin’s followers believe were proof of his exceptional powers. He laid a curse on Giyasuddin when the sultan poached the saint’s workmen to construct his fortress city of Tugluqabad. ‘Ye base Gujjar, Ye Rahi Ujar’ (let it belong to the Gujjar or let it remain in desolation), he prophesied when Tugluqabad was completed, and Tugluqabad has been a derelict city.

Acts like these nettled Giyasuddin no end and he promised to teach the saint a lesson on his return from a campaign in Bengal. When the disciples of the saint got wind of this, they advised Nizamuddin to flee Ghiyaspur. He didn’t. Instead, he replied, “Hunooz Dilli door ast (Delhi is still far away)” – a statement rendered true when the tent under which Giyasuddin was resting, when he was outside Delhi, collapsed, killing him instantly.

Although a few statements like these came true, Nizamuddin himself did not believe in karamat or miracles, and his life is not credited with any. He remarks in the Fawaid-ul-Fuad, revealing secrets, and performing miracles, are a hindrance in the path. True work consists of maintaining love.

And of that love, the saint had plenty. At a time when almost all non-Muslims were considered enemies of Allah, Nizamuddin preached a gentler doctrine of reconciliation. His love and humanitarianism extended to all and it is something that is noticeable even today in the mix of pilgrims who throng his tomb. The small knots of pilgrims hanging around on the verandah surrounding his tomb are from all over India and are of different religions; there are Hindus and Sikhs, people from Chhattisgarh, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu.

The setting – both the interiors and the exteriors – is anything but what one associates with the austerity of the saint. The fluted marble columns support cusped arches, covered with gold, pink, and green floral designs at the entrance to the tomb. The walls of the chamber are pierced by elaborately carved marble jaalis and glass chandeliers hang from a red, blue, and gold painted ceiling. However, as I was to learn later, all this ornamentation and the surrounding buildings were the work of the Mughals, who craved to be associated in some manner with the saint.

Nizamuddin died on April 3, 1325, leaving behind a line of khalifas (disciples) best-known of whom were Amir Kusrau, the famous poet-mystic and Nizamuddin Dehlavi, the successor of the saint. In the manner of many great saints, Nizamuddin foresaw his own death and prepared his followers well in advance. The Siyar-al-auliya recalls his last days:

For 40 days before his death, the sheikh ate nothing. As the end approached, he said, “The time of prayer has come. Have I said my prayers?” He instructed his servant Iqbal to sweep his room clean. As soon as he had cleaned the room, the servant pleaded, “After you have gone what will become of us?” “The charity that arrives at my grave will suffice for you,” rejoined the saint.

I looked at my watch. It was six pm, and the stream of pilgrims was thinning. But the famished looking beggars and the hangers-on I had seen earlier remained. They were going nowhere. The call for prayer went up in the nearby Jammat khana, the mosque where the sheikh prayed.

Almost simultaneously, a bell rang in a corner and a line began to form. The beggars and the hangers-on were being fed, no doubt from the charity that had been collected. Sheikh Nizamuddin’s words were indeed prophetic.

Arun Ganapathy is a freelance writer and trainer based in Delhi. His travels and interests in sacred sites have taken him from Bhutan to Mexico Contact: ganapathy_arun@yahoo.com

We welcome your comments and suggestions on this article. Mail us at editor@lifepositive.net

To read more such articles on personal growth, inspirations and positivity, subscribe to our digital magazine at subscribe here

Life Positive follows a stringent review publishing mechanism. Every review received undergoes -

- 1. A mobile number and email ID verification check

- 2. Analysis by our seeker happiness team to double check for authenticity

- 3. Cross-checking, if required, by speaking to the seeker posting the review

Only after we're satisfied about the authenticity of a review is it allowed to go live on our website

Our award winning customer care team is available from 9 a.m to 9 p.m everyday

The Life Positive seal of trust implies:-

-

Standards guarantee:

All our healers and therapists undergo training and/or certification from authorized bodies before becoming professionals. They have a minimum professional experience of one year

-

Genuineness guarantee:

All our healers and therapists are genuinely passionate about doing service. They do their very best to help seekers (patients) live better lives.

-

Payment security:

All payments made to our healers are secure up to the point wherein if any session is paid for, it will be honoured dutifully and delivered promptly

-

Anonymity guarantee:

Every seekers (patients) details will always remain 100% confidential and will never be disclosed