- Home

- Archive -Feb 2021

- SAVING THE PAST. . .

SAVING THE PAST FOR THE FUTURE

Asha Kasbekar makes a strong and convincing case for digitally preserving India’s priceless ancient scriptures

Last year, during the monsoons in India, the ground floor of a 150-year-old library in Sangli, Maharashtra, was completely inundated. The Sangli Jilha Nagar Vachanalay library, which was crammed from floor to ceiling with around 40,000 old books and manuscripts, was submerged under eight feet of water for three whole days.

Along with the venerable library’s precious collections of old books, biographies, and autobiographies were many rare, handwritten manuscripts that dated back several centuries, all of which were reduced to pulp.

Sangli, known for its turmeric and sugarcane, sits peacefully beside the river Krishna. That the city suffered such catastrophic flooding last year is proof if a proof is needed, of the growing threat of climate change.

While there has been growing global awareness about the calamitous loss of plant biodiversity and animal species due to the combined causes of human activity, global warming, and climate change, the loss of the nation’s intellectual legacy due to the very same causes have been far less examined.

India has a very long and illustrious history of sophisticated philosophical thought. Many of these profound intellectual musings on metaphysics and the nature of man and God were inscribed on scrolls made from palm leaves. While elsewhere in the world, vellum, papyrus, or paper was used for writing, in India and South Asia, the preferred material for writing was the palm-leaf scroll.

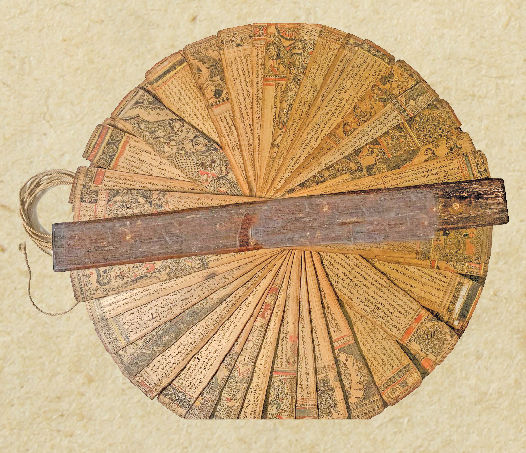

Palm Leaf Scrolls

For centuries, individual palm leaves were dried, cured, then cut into rectangular shapes, and made ready for writing on. Letters were inscribed with a knife-like pen on these palm-leaf scrolls; colourings were then applied across the surface and subsequently wiped off, leaving the ink in the incised grooves to reveal the text. The sheets were then tied together with a string that passed through holes in each page and tied together to make books.

Such palm-leaf scrolls, with their distinctive rectangular shapes, were used from ancient times right until the 19th century. Each scroll could last anywhere from just a few decades to 600 years before falling victim to dampness, insect activity, mould, and human handling. When these scrolls began to show signs of deterioration, the texts were painstakingly recopied in order to replace them.

The organic material used in the manufacture of these scrolls inevitably deteriorated with the passage of time. Made from plant carbohydrates, they were vulnerable to the environmental effect of sunshine and humidity as well as infestations of insects, silverfish, mould, and other biological factors. Natural disasters like floods (as seen in Sangli) and earthquakes as well as man-made ones such as wars and the destruction of libraries and temples where these scrolls were housed also contributed to the loss of these valuable manuscripts.

One of the oldest surviving Sanskrit collections of manuscripts on palm leaves is the Paramesvaratantra, a Shaiva Siddhanta text dating from the 9th-century CE. Shaiva Siddhanta is one of the tantric theological schools that taught the worship of Siva as ‘Supreme Lord’ (the literal meaning of Paramesvara). Dated to about 828 CE, this palm leaf scroll is preserved by the University of Cambridge Library.

Although the Paramesvaratantra is so far unpublished, a digitised copy exists in the digital library of the Muktabodha Indological Research Institute (www.muktabodha.org) as part of its Shaiva Siddhanta collection. The small non-profit organisation is dedicated to the digital preservation of India’s scriptural heritage, in particular, the texts of Kashmir Shaiva, Shaiva Siddhanta, and the Vedas. It makes its collections freely available to scholars and seekers throughout the world.

“Rich Past, Poor History”

While advanced countries of the world have taken great care to preserve their cultural heritage, in contemporary India, there exists a serious lack of awareness of the nation’s priceless heritage, and intellectual treasures in fragile scrolls lie neglected in unloved corners. In Celluloid Man, Shivendra Singh Dungarpur’s documentary on the great film archivist P.K. Nair, a historian laments that “India has a rich past but a poor history.”

For centuries, temples, libraries, and families tried to safeguard their collections by using traditional methods of preservation. These included, among others, the use of indelible ink, wrapping the scrolls in cotton dipped in turmeric water for its antimicrobial qualities, and exposing the manuscripts to the sun on special days when its rays were considered to contain special antimicrobial qualities.

But the loss of such expertise has led to fewer scrolls being recopied. Also, as extreme weather events become more frequent and severe – which they inevitably will – preserving the millions of fragile manuscripts scattered across the country is going to be well-nigh impossible. However, even if all the physical books and manuscripts themselves cannot be preserved for future generations, then digital technology can be mobilised to save, at least, the contents of these writings and ensure that the great knowledge and wisdom of our ancestors, contained within these texts, are not lost to the world forever.

The beauty of IT

Digital technology offers myriad advantages for the preservation of the past. First of all, it is not subject to the merciless vagaries of the weather, and, with sufficient backup copies, can insure against any accidental digital loss. Furthermore, the possibility of digital dissemination obviates the need for physical displacement. With everything available at the click of a button, no longer would scholars and researchers have to trudge to far-flung, and often, inaccessible temples, monasteries, and libraries (both public and private) to look for ancient texts. In fact, free and easy dissemination to every corner of the world at all times, as offered by Muktabodha and other such charities, has encouraged the study of India’s great philosophical legacy throughout the world.

The European colonial powers left their colonies—but not before taking away many rare important works of art, artefacts, books, and manuscripts. Since memory and the past are crucial in the formation of national identity, many former colonies have been buying back their patrimony. The beauty of digital technology is that it does not dispossess the owner or custodian of his or her rightful possessions. Instead, by creating copies of the original, it safeguards the contents of the original work for future generations.

India—a country that has already given the world the wisdom of yoga, meditation, and Ayurveda (to name but a few)—also boasts of a sophisticated IT industry. The coming together of ancient wisdom and cutting-edge 21st-century technology could power the world’s next intellectual renaissance.

Last year, mercifully, the monsoon rains were less destructive than the ones before, but weather patterns have been changing significantly. To protect against the destruction of India’s splendid past, discovery, digitisation, and dissemination remain the keys to safeguarding India’s great heritage.

So, let us save the pandas and the rainforests. But let us also save texts like the Paramesvaratantra!

To read more such articles on personal growth, inspirations and positivity, subscribe to our digital magazine at subscribe here

Life Positive follows a stringent review publishing mechanism. Every review received undergoes -

- 1. A mobile number and email ID verification check

- 2. Analysis by our seeker happiness team to double check for authenticity

- 3. Cross-checking, if required, by speaking to the seeker posting the review

Only after we're satisfied about the authenticity of a review is it allowed to go live on our website

Our award winning customer care team is available from 9 a.m to 9 p.m everyday

The Life Positive seal of trust implies:-

-

Standards guarantee:

All our healers and therapists undergo training and/or certification from authorized bodies before becoming professionals. They have a minimum professional experience of one year

-

Genuineness guarantee:

All our healers and therapists are genuinely passionate about doing service. They do their very best to help seekers (patients) live better lives.

-

Payment security:

All payments made to our healers are secure up to the point wherein if any session is paid for, it will be honoured dutifully and delivered promptly

-

Anonymity guarantee:

Every seekers (patients) details will always remain 100% confidential and will never be disclosed