- Home

- Archive -May 2011

- Homes after you. . .

Homes after your heart

- In :

- Personal Growth

May 2011

By Satish Purohit

Architects of the New Age are creating organic, sustainable, energy efficient houses that draw on local traditions of construction, craft and labour.

|

From what space within does a person on the path ideally design, remodel or furnish the space that he or she calls home? What materials does one consider appropriate in its creation? How does one shape the spaces by using walls, roofs, floors, windows, doors, columns and stairs so one feels physically rested, emotionally rejuvenated and spiritually uplifted? Are there ways to shape home spaces to facilitate respectful communication both within the family as well as with neighbours, promote intimacy, guard privacy, balance conflicting and competing energies between family members and foster inclusiveness in the neighbourhood?

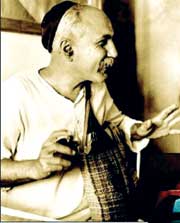

While several architects have attempted to answer these questions in the positive through their work in India, some like Nari Gandhi, Balkrishna Doshi and Laurie Baker and others associated with Auroville in Pondicherry have succeeded in doing so in ways that makes them the torchbearers of a New Age in architecture.

These men and women have been pointing out the folly of constructing through conventional methods that rely on cement and steel that are not merely heavy on the pocket, but also damage the environment when they are produced, used and discarded.

“The basic elements of a modern building like cement, steel, glass, ceramic, plastic and synthetic fibre are not connected to nature in the same way mud, brick, lime, thatch, timber and grass are. The industrial elements are what we know as waste, insofar as they aren’t, to use a trendy word, biodegradable. They also produce non-disposable waste. In its search to be permanent and ‘maintenance-free’, architecture has lost its capacity to be regenerative, and therefore, ecologically sensitive,” explains RL Kumar of the Centre for Vernacular Architecture, a co-operative of building craft persons established in 1989.

We also have an example of the work of masters like Hassan Fathy of Egypt (revived traditional Egyptian mud architecture), Nader Khalili of Iran (developed a super mud-adobe system of construction in 1984, in response to NASA’s call for designs for human settlements on the Moon and Mars), Geoffrey Bawa of Sri Lanka (Sri Lanka’s most prolific and inventive architect, who initiated what is known as tropical modernism, and created beautiful sustainable architecture when the term had not been coined) and Christopher Alexander in the US who asserts that anyone can create beautiful holistic architecture if one lets one’s heart lead one’s head. He boldly advocates the use of feelings as a reliable guide for judging good architecture from bad.

Nari Gandhi, New Age architect Nari Gandhi, New Age architect‘We should be happy with every little thing we have. We should build in the style of our ancestors with a little change here and there. ‘ |

Organic architecture

Described variously as vernacular, organic or sustainable architecture, the work of these architects marries traditional methods of construction and locally available resources with modern technology to address local needs and circumstances. Their work honours the environmental, cultural and historical context in which it exists.

“Vernacular architecture values labour over capital-intensive materials that are mass produced and massively subsidised by the government. We need vernacular architecture, which is humane and retains the human touch, because it relies on locally available materials and on craftsmen who work with their hands. No wonder the structures created by such architecture are closer to nature, history and tradition. These insights are not really new – Gandhiji had pointed all this out to us decades ago. All we need to do is follow his footsteps,” explains RL Kumar.

The good news is that while the cost of conventional construction varies from Rs 900 to Rs 1,400 a square foot in metropolitan cities like Mumbai, holistic homes can often be cheaper. “Our team has created beautiful houses from mud, random rubble and exposed brick for as little as Rs 300 a square foot that are long-lasting, functional and energy-efficient. However, the costs keep changing. It will all depend finally on the sort of house you want,” Kumar adds.

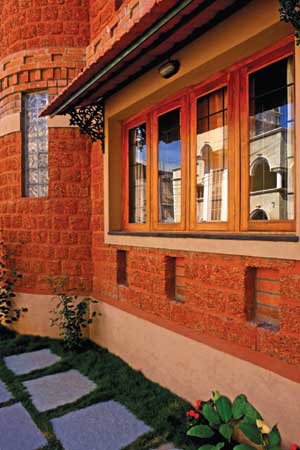

Houses designed by Kumar’s team rely on superior masonry that uses fewer bricks, provides better insulation from the Indian summer and does away with wall-plaster and finishes that can account for as much as 30 per cent of the cost of a house. Kumar bases his practice in part on the principles laid down by Kerala-based English architect Laurie Baker, whose 70-page cost-saving manual on home building is available on his official website www.lauriebaker.net.

A verdant roof garden is not just a thing of beauty, it can also keep the roof cool A verdant roof garden is not just a thing of beauty, it can also keep the roof cool |

Eighty-year-old Didi Contractor, a self-taught architect based in Himachal Pradesh, who has been building beautiful cottages from mud, believes homes made with hands have a certain ‘emotional content’ that concrete houses lack. “During building, I am very conscious of where the money is going. If I’m buying cement, the money is going up and away. But if I am making mud bricks the money is going down to support someone who can’t find other work here. It is a luxury to be able to do that but it helps overcome, to some extent, the inequity within society. Social costs are very high on my agenda,” said Contractor in an illuminating interview with architect and photographer, Joginder Singh.

Living in harmony

There is, of course, more to holistic architecture than the use of appropriate materials. It also has to ensure that the human motions and emotions that in their totality make for living – praying, eating, sleeping, defecating, making love, socialising, playing, cooking – and the shape of spaces in the built environment that people inhabit are not at variance.

Seminal architectural thinker Christopher Alexander points out that people living in certain spaces cannot feel whole or alive no matter how much they work on themselves.

| In these maze-like meandering city streets, my love We too shall own a home the windows will open into the blue sky and the skies will spill into our home – Lyrics by Gulzar for Gharonda (1977) | ||

“There is a myth. sometimes widespread, that a person need only do inner work, in order to be alive like this… Some kinds of physical and social circumstances help a person come to life. Others make it difficult,” writes Christopher Alexander in his opus, The Timeless Way of Building.

Holistic spaces, in short, allow people to go through the motions that make for living effortlessly and also fulfil deep unstated psychological needs for privacy, intimacy and for meaningful communication with the family as well as the neighbourhood. If the spaces are unholistic in design as well as use of materials, they demand heavy sacrifices from people who live there. That people inhabiting such spaces make these compromises, big and small, and manage to be happy nevertheless, points to the human genius for adaptation.

Tao of architecture

Ever wonder why so many new buildings leave us cold? There is often something about them that makes us feel incomplete and unfulfilled when we are in and around them. Yet other buildings and spaces, built, or as they are found in nature, move us and make us feel alive. It could be a well-lighted high street with a row of shops or a wall at seat height facing the sea or even a beautiful entrance to a cottage.

Christopher Alexander begins The Timeless Way of Building by asking these questions. He says the answer to what moves us and what does not depends on the extent to which a structure adheres to what he describes as the ‘timeless way of building’.

At the heart of his essay is the insight that a space gets its character from the repetitive patterns of events that keep happening there. If the place, for instance, is a public garden in a city, it would witness events like playing of children, young couples engrossed in quiet moments of intimacy and young mothers gossiping as they watched over their children playing. It would also include non-human events like birds coming to feed on worms in the soil or the flowing of a stream. If these patterns of events are not supported by the built environment, the men, women and children who visited the park would not feel fulfilled. This would make the place dead like so many contemporary spaces. If the swings were, for instance, built on a spot that did not allow the young mothers to look over the children as they played, the mothers would constantly be in anxiety. If the benches were placed too close to the entrance, they would prove to be a constant source of distraction for the lovers seated on them. Thus, says Alexander, the patterns of events have to be matched by patterns in space that allows them to unfold without effort. Good architecture, in short, allows all energies that are generated in the space to be resolved effectively.

The friendly neighbourhood baithi chawl in Mumbai The friendly neighbourhood baithi chawl in Mumbai |

In the book, Pattern Language, Alexander, along with co-authors, lists 253 patterns that he believes are capable of creating towns, streets, markets, homes, and even rooms and windows that help in making people ‘alive’. Pattern 164, for example, is ‘street windows’, which says that buildings situated on the streets should have windows that open into the street if the people living in the building are to feel fulfilled and alive. “A street without windows is blind and frightening. And it is equally uncomfortable to be in a house which bounds a public street with no window at all on the street.

Where buildings run alongside busy streets, build windows with window seats, looking out onto the street. Place them in bedrooms or at some point on a passage or stair, where people keep passing by. On the first floor, keep these windows high enough to be private.”

Pattern 253 titled ‘pools of light’ says that homes should not have uniform lighting throughout a room or house as is the case with most city apartments but should instead have dappled light. “Uniform illumination – the sweetheart of the lighting engineers – serves no useful purpose whatsoever. In fact, it destroys the social nature of space, and makes people feel disoriented and unbounded…. place the lights low, and apart, to form individual pools of light which encompasses chairs and tables like bubbles to reinforce the social character of the spaces which they form. Remember that you can’t have pools of light without the darker spaces in between.”

All patterns in an architectural language, says Alexander, are related to each other as all words of a language are related to each other. Anyone, not just a specialist, who understands pattern language can create architecture that lives – be it a room, a public building or a home.

Architecture and happiness

Several examples of individuals as well as families transcending the limits placed on them by their environment can be found in Mumbai’s vibrant baithi chawls. An estimated 60 per cent of Mumbai’s population lives in informal housing (not designed by architects) that are pejoratively referred to as slums. Most families who live in these tenements, which can be as small as 80 square feet, depend on public toilets for answering nature’s calls, share taps supplying municipal water and battle water-logging during the monsoons. The rooms are rarely cross-ventilated and have openings on one side of the four walls that make the house. Despite all these limitations, families that move away from the chawls speak with nostalgia of the time spent there. Ashutosh Tiwari (22), an IT professional who grew up in such a baithi chawl in Mumbai, says, what the chawls lack in privacy they make up in community spirit and liveliness. “It is not that residents don’t have their share of squabbles but people tend to keep all their differences aside during times of crises. Neighbours are quick to react during medical emergencies because everyone is on the ground floor and doors and windows are rarely closed during the day,” Tiwari says. In a way, the baithi chawls and jhuggis or jhopadpattis as they are known in Mumbai, attempt to recreate the ambience of the village in an urban setting somewhat lighter of the baggage of caste and biradari.

“Women meet at communal taps to gossip and neighbours keep a watchful eye on kids who wander freely from house to house. The older children keep an eye on the younger ones, and kids make the best of the limited space for playing,” Tiwari adds.

Community leaders in some baithi chawls, mindful of the potentially explosive results of living at such close quarters, have actively participated in mohalla committee initiative that keeps hot-headed elements in check during times of communal conflagrations.

Many lessons in community living and adaptation used by baithi chawls can be used by all individuals and families.

Lofts: With as many as 14 people living in a single 150 square feet baithi chawl, families construct an additional storey wherever possible and a loft where it is not. This also resolves the problem of privacy for couples who are starved for intimacy.

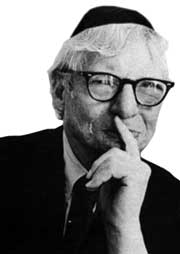

Louis Kahn, Louis Kahn,world renowned architect ‘Architecture is the reaching out for the truth |

Flexible spaces: With space always in short supply, heavy chunky furniture is shunned. Diwans that can be used as beds in the night, folding chairs and folding aluminium ladders are preferred. All free floor space is used for sleeping at night. Space near sole doorway abutting lane outside the house is used for washing clothes in the morning, winnowing grain in the afternoon and for finishing job work taken from cottage industries nearby.

Creative use of space: Walls are rarely allowed to go bare. Shelves house family deities, books and utensils. Long thin deep rooms have a living space followed by a kitchen space followed by a sleeping space. The spaces are often separated by half-walls that give privacy and also allow for the stale air to exit. Industrial exhaust fans are installed at the sole outer wall of the tenement.

Families, rarely less than four strong, respond to challenges imposed by shortage of space with immense creativity and perseverance. They plant flowers, celebrate festivals and organise feasts jointly. Expenses for cleaning communal toilets are shared as are costs of creating places of worship.

Holistic use of apartments

Upwardly mobile families tend to move from chawls to flats in multi-storey buildings. Often, they are so happy to have arrived that they do not make many demands of the developers. “Years ago, all apartments had ventilators. Today, builders have reduced ceiling heights and there is no space for ventilators,’ says Akhtar Chauhan, the architect and director of the Rizvi College of Architecture. ‘Warm air exhaled by residents tends to rise to the ceiling where it is thrown back at the residents by ceiling fans, which makes them cough through the year. This also makes summers a difficult time, forcing families to buy air conditioners. A room should have openings for sunlight on at least two sides of the room for it to be suitably bright. Very few rooms being constructed today really do. All this can change if buyers become conscious that despite spending lakhs of rupees they are being cheated of something as basic as clean air,” adds Chauhan, who points out that city apartments can use the wisdom of traditional courtyard houses with profit.

“A courtyard house is an open space with rooms around it. We should incorporate the courtyard into our apartment complexes because they are suitable for our environment. We have the precedents set by architects like Laurie Baker and Charles Correa that point in that direction. We can build on their work,” Chauhan says

Often, financial, societal and other factors land people in flats that suffer from all the limitations listed above and more, like the lack of gardens, playgrounds and open spaces around buildings. Few flats have balconies, that function as halfway spaces between the indoors and outdoors.

However, even in such constrained situations, there are steps one can take to make the surroundings more holistic. Sandeep Sonigra of the Orange County foundation, a green business that constructs environmentally sound homes, has developed several multi-storey apartment complexes in Pune that are nearly self-sufficient in its energy requirements. The complexes uses solar and wind energy for its energy requirements, recycle their waste, treat their own sewage. His buildings use eco-friendly lime as the base material for its bricks, mortar, plaster and paint.

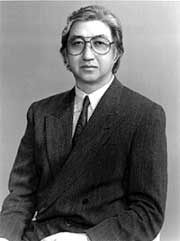

Ayn Rand, Novelist Ayn Rand, Novelist‘A building has integrity just like a man. And just as seldom. |

Tips for flat buyers

“Families should avoid living in apartments higher than tree tops, which of course, means that skyscrapers should be avoided,’ explains architect and professor, Pradnya Chauhan. ‘One, it is not a good idea to live in a place that towers over vegetation in the neighbourhood, two, the playgrounds, if there are any, are too far below for the children to access with ease. Three, they make it difficult for parents to keep the children in their visual and aural radar,” she adds.

While not all of us have the luxury of constructing our own houses there are steps one can take to make existing homes more sustainable and ecologically sound.

Anand Achari, architect and sustainable design consultant, explains that flat-owners should aim at making optimum use of the five elements: water, air, energy, land and ether. Houses where these elements are in a state of imbalance need to be modified so balance is restored. “If it is a new flat that one is buying, the first thing I would look at is the green spaces (the land element) around my house. If the green cover is insufficient, I would plant trees to shade my house. Roofs that get heated during summer can be made more comfortable to live under if we paint them with high-albedo paints that reflect the heat back into the atmosphere,” Achari says.

The Jayashree residence in Ulsoor, Bangalore, built by RL Kumar The Jayashree residence in Ulsoor, Bangalore, built by RL Kumar |

Many apartment societies maintain rooftop gardens that are aesthetically pleasing and also shield flat-owners living in the topmost storeys from the summer heat. A vegetable garden that uses all the organic waste generated by the residents for composting is also a good idea. You probably have security personnel with a background in farming who would willingly double up as gardeners for a small fee. You may also get in touch with Adrienne Thadani and Karen Peters of www.unltdindia.org who organise workshops on urban farming in Mumbai.

Achari maintains his own little garden in his Mumbai home where he disposes of all his organic waste. “If you have a flat that does not receive enough natural light, you would want to modify the openings in the rooms to get more sunlight in. This also works for homes that are not sufficiently airy. One can facilitate cross ventilation by modifying the openings suitably,” Achari said, adding that the holistic outlook could be extended to the purchase of electrical appliances and fixtures like lights and fans. “Today, high-performance energy-efficient lights and fans are widely available. Do not settle for less. Again, with taps, one can actually choose hardware that gives low-flow. You would be surprised at how much water you can save with good design. Showers result in a criminal waste of water. Using buckets and mugs is the sensible thing to do,” Achari added. “I would separate dry and wet waste and all organic waste would be composted for my kitchen garden. Even people starved for space can grow something in some pots. All dry waste would be sorted out to be given to the raddiwala. Considering that Mumbai alone creates 7,000 tonnes of waste a day, what a difference it would make if all of us followed this approach,” says Achari.

One can use eco-paints that ensure a healthier body and greener environment to live. Made from plant sources and minerals, eco-paints are non-toxic with zero VOC (Volatile Organic Content) and have no odour and can be tinted to any colour (Visit www.ecoindia.com or www.auropaintindia.com for details).

Laurie Baker and home building

The Rock Palace of Shibam has been in occupation since it was built in 1220 |

After India gained independence, architect Laurie Baker (March 2, 1917 –April 1, 2007), a British national, stayed on in India, partly because he thought that he could play a larger role in constructing houses for India’s homeless millions than he could in England, and Mahatma Gandhi, whom he admired greatly, had urged him to do so. “I believe that Gandhiji is the only leader in our country who has talked consistently with common-sense about the building needs of our country. One of the things he said that impressed me and has influenced my thinking more than anything else was that the ideal houses in the ideal village will be built on materials which are all found within a five-mile radius of the house. I used to argue to myself that of course he probably did not intend us to take this ideal too literally. But now, in my 70s and with 40 years of building behind me, I have come to the conclusion that he was right, literally word for word,” Baker was forced to concede.

Baker’s advice to anyone who wishes to build a house somewhat echoes the Vedantic dictum: Neti, neti (not this, not this).

“Building houses is a costly business these days. A lot of the current expenditure is on unnecessary fashion frills and designs. Much money could be saved merely by using common sense, along with simple established, tried and tested building practices. Every item that goes to make up a building has its cost. So, always ask yourself the question: is it necessary? If the answer is ‘no’, then don’t do it!” Homes designed by Laurie Baker shun reinforced cement concrete, use no external plaster and very little internal plaster. He preferred jaalis to windows for ventilation and used light-weight sloping roofs instead of the flat concrete ones that have brought the expression ‘matchbox architecture’ into existence. In Baker’s houses the shelves and seating are inbuilt into the structure and the use of ‘rat-trap’ bond in brick-laying ensures that fewer bricks are used, and the walls are better insulated from the heat of the summer.

Yoshio Taniguchi, Yoshio Taniguchi,Prominent Japanese Architect ‘Architecture is basically a container of something. I hope they will enjoy not so much the teacup, but the tea. |

He advocated the use of self-supporting arches instead of concrete lintels that use cement and steel to support door and windows and never cut standing trees on a site. (He once saw a young mango tree being cut at a site where he was designing homes for IAS officers and never returned to the spot).

He was a master of adaptive reuse. Nothing went to waste as abandoned doorways, windows, hardware and timber from old structures were beautifully incorporated into the new homes. Baker spoke strongly against the love for facadism. “I just think it is plain stupidity to build a brick wall, plaster it all over and then paint lines on it to make it look incongrous.

To read more such articles on personal growth, inspirations and positivity, subscribe to our digital magazine at subscribe here

Life Positive follows a stringent review publishing mechanism. Every review received undergoes -

- 1. A mobile number and email ID verification check

- 2. Analysis by our seeker happiness team to double check for authenticity

- 3. Cross-checking, if required, by speaking to the seeker posting the review

Only after we're satisfied about the authenticity of a review is it allowed to go live on our website

Our award winning customer care team is available from 9 a.m to 9 p.m everyday

The Life Positive seal of trust implies:-

-

Standards guarantee:

All our healers and therapists undergo training and/or certification from authorized bodies before becoming professionals. They have a minimum professional experience of one year

-

Genuineness guarantee:

All our healers and therapists are genuinely passionate about doing service. They do their very best to help seekers (patients) live better lives.

-

Payment security:

All payments made to our healers are secure up to the point wherein if any session is paid for, it will be honoured dutifully and delivered promptly

-

Anonymity guarantee:

Every seekers (patients) details will always remain 100% confidential and will never be disclosed

Self-taught architect Didi Contractor speaks to Life Positive on the art and craft of building holistic homes

You build with mud. Can one build such houses in cities like Mumbai and Bangalore or Delhi?

Building, like most other human activities, makes destructive demands on nature and disturbs ecological processes. In the past nature had the upper hand and human activities had to comply with nature’s demands or risk extinction.

Architects in each situation can try to create ways to do the least damage.

Any holistic or ecological approach has to be sensitive to diversity: the particular character and the different problems of each place, each building site. Different materials and technologies become ‘appropriate’ in different contexts. Here in rural Himachal Pradesh I use local building methods and harvest materials such as mud and bamboo from each site. In any other place I would explore the time-tested building traditions of that place. In Bangalore, Chitra Vishvanath, for instance, (www.biome-solutions.com) uses compressed bricks made from the earth dug from basements at the site.

How do houses designed by you compare with those constructed with concrete in terms of durability, functionality, repair costs and cost of construction?

Various forms of cost should be considered. Monetary costs, which are by nature easy to measure, only affect individual purses and pockets. Ecological costs affect everyone, and even the as yet unborn will have to pay. Concrete has a very high ecological cost. The monetary cost of the houses I design can be up to one third lower but my main concern is to lower the ongoing ecological costs. Good design can save energy at the time of construction and throughout the life of the building. The houses I design have proved durable and are easy and cheap to repair. Repair costs for conventional buildings are VERY much higher but conventional buildings can survive longer without repair.

Concrete houses cost around Rs 900 – Rs 1,400 psqft. How much do your houses cost?

There are costs at the time of construction and there are ongoing energy costs for the duration of the life of the building. I can usually build the same carpet area for one-third the cost, but I urge clients to spend that difference on energy saving and on the quality of amenities.

What is your advise to city-dwellers who can only afford small apartments?

Energy and ecology affect us all; our common (holistic) environment is experienced by us all. City dwellers may not have the luxury of living in ecologically constructed buildings but we all contribute to our surrounding environment by the way we live. By being sensitive to common needs in common spaces and being active in addressing such common issues as conservation, pollution, poverty and waste we can contribute to the (holistic) welfare of all.

Yemen’s Skyscrapers of Mud

The city of Shibam in Yemen has been described as ‘the Manhattan of the desert’. Built primarily from mud, the highest house in the city of Shibam is eight-storeys high and the average is five. While repairs are required annually, some of the multi-storey houses have been continuously occupied for over four centuries now. The impressive structures for the most part date from the 16th century, following a devastating flood of which Shibam was the victim in 1532-33. However, some older houses and large buildings still remain from the first centuries of Islam, such as the Friday Mosque, built in 904, and the castle, built in 1220.

Source: UNESCO