- Home

- Archive -Mar 2002

- INNER WARRIORS

INNER WARRIORS

- In :

- Personal Growth

March 2002

By Clifford Sawhney

By In the days of yore before exercise systems became a form of combat as martial arts, they tapped the mysterious power of chi for self-healing, self-discovery, even self-realization. With the right attitude and techniques, they still can

The world's oldest civilizations like China and India have a history of martial arts dating back at least 2,000 years. While it is impossible to pinpoint the precise origins of martial arts, one system from Kerala claims to be the 'mother of all martial arts'�kalaripayattu. Legend has it that around the 4th century AD, Parasurama brought it to earth from heaven. Of Sanskrit lineage, the word kalari denotes 'place of training' and payattu signifies 'training in the martial arts'. Based on vastu shastra principles, the kalaripayattu arena is dug six feet below the ground over an area of 42 feet in length in the east-west direction and 21 feet in breadth. The most well known kalari is CVN Kalari in Thiruvananthapurm, India. Says Murugan Gurukkal, a Delhi-based practitioner: ''Kalari gurukulas impart knowledge of Vedas and Upanishads as well as modern science and mathematics. The training period is five to six years. Kalaripayattu is the only martial art in the world where the art of healing�marma chikitsa�is also taught. The use of herbal oils and massage are part of this.'' Murugan's Nithya Chaithanya Kalari Sanghom has been imparting training in kalaripayattu in Delhi since 1993. ''Meditation and yoga are taught during training. These are essential because when using weapons, maximum concentration is required. Meditation is also helpful in marma chikitsa in which, by touching a particular point in the body a person can be knocked unconscious, paralyzed or even killed. This is the last part of the training and is not taught to everybody,'' says Murugan. A spectacular martial art, kalaripayattu is characterized by high jumps, kicks and swordsmanship. Practitioners are also trained in the use of weapons like staff, spear, dagger, sword, mace and shield after six years. The discipline is said to systematize the flow of energy (prana) in the body, mold character, increase self-confidence and help cure and control ailments. Kalaripayattu demonstrations include physical exercises and mock duels, armed and unarmed. Chinese martial arts are said to have originated from kalaripayattu when Bodhidharma took the art to China around 520 AD. Some contest this claim. Counters Rashid Ansari: ''Although there's a lot of hype on how the martial arts went from India to China, I don't agree with this. I practice Chinese styles and find no similarity with Indian styles. The complexity of the empty hand system of China makes me think otherwise. That Bodhidharma took martial arts from India to China is a myth. People also confuse the origin of martial arts with the Shaolin Temple. Martial arts have been there for over 2,000 years. There's no doubt, though, that China, India and Korea are the oldest places to practice martial arts.'' ''In March and April every year, kalari competitions are held in Kerala,'' says Murugan. ''Awareness of this art is rising. We were recently invited to the Bhopal Lok Rang Festival held between January 26 to 28 and gave demonstrations of kalaripayattu.''

The world's oldest civilizations like China and India have a history of martial arts dating back at least 2,000 years. While it is impossible to pinpoint the precise origins of martial arts, one system from Kerala claims to be the 'mother of all martial arts'�kalaripayattu. Legend has it that around the 4th century AD, Parasurama brought it to earth from heaven. Of Sanskrit lineage, the word kalari denotes 'place of training' and payattu signifies 'training in the martial arts'. Based on vastu shastra principles, the kalaripayattu arena is dug six feet below the ground over an area of 42 feet in length in the east-west direction and 21 feet in breadth. The most well known kalari is CVN Kalari in Thiruvananthapurm, India. Says Murugan Gurukkal, a Delhi-based practitioner: ''Kalari gurukulas impart knowledge of Vedas and Upanishads as well as modern science and mathematics. The training period is five to six years. Kalaripayattu is the only martial art in the world where the art of healing�marma chikitsa�is also taught. The use of herbal oils and massage are part of this.'' Murugan's Nithya Chaithanya Kalari Sanghom has been imparting training in kalaripayattu in Delhi since 1993. ''Meditation and yoga are taught during training. These are essential because when using weapons, maximum concentration is required. Meditation is also helpful in marma chikitsa in which, by touching a particular point in the body a person can be knocked unconscious, paralyzed or even killed. This is the last part of the training and is not taught to everybody,'' says Murugan. A spectacular martial art, kalaripayattu is characterized by high jumps, kicks and swordsmanship. Practitioners are also trained in the use of weapons like staff, spear, dagger, sword, mace and shield after six years. The discipline is said to systematize the flow of energy (prana) in the body, mold character, increase self-confidence and help cure and control ailments. Kalaripayattu demonstrations include physical exercises and mock duels, armed and unarmed. Chinese martial arts are said to have originated from kalaripayattu when Bodhidharma took the art to China around 520 AD. Some contest this claim. Counters Rashid Ansari: ''Although there's a lot of hype on how the martial arts went from India to China, I don't agree with this. I practice Chinese styles and find no similarity with Indian styles. The complexity of the empty hand system of China makes me think otherwise. That Bodhidharma took martial arts from India to China is a myth. People also confuse the origin of martial arts with the Shaolin Temple. Martial arts have been there for over 2,000 years. There's no doubt, though, that China, India and Korea are the oldest places to practice martial arts.'' ''In March and April every year, kalari competitions are held in Kerala,'' says Murugan. ''Awareness of this art is rising. We were recently invited to the Bhopal Lok Rang Festival held between January 26 to 28 and gave demonstrations of kalaripayattu.''

The cool, crisp winter air had all the early morning walkers relaxed and invigorated in a Delhi park. A group practicing yogasanas and some dozen-odd members of a laughter club also felt recharged. In another corner of the park, a group of youngsters were practicing their katas with seemingly boundless energy. Each group was in the park for individual goals, but all were doing one thing in common: boosting their chi. All life in the cosmos is animated by chi, which is a 'life-force' or 'vital energy' that is said to be the power that governs the universal power. Says martial arts exponent Rashid Ansari: 'Chi (pronounced 'qi') is the Chinese word for life-force or cosmic energy. The Japanese call it 'ki', we Indians call it 'prana' and 'kundalini', the Apache 'diyin' and the pygmies 'mana'. Chi is the animating power that flows through all living things. A living person is filled with it; a dead person has none. It is also the life energy one senses in nature, in the cosmos around us. It is this indwelling force that manifests as the feel of a direction or a pattern frozen within an instant. Hence, in the East and specifically in the martial arts, physical action and the indwelling life force cannot be disassociated.' Ansari claims that while all living beings have chi, it is the cultivation, expansion, harnessing and use of chi in martial arts that merits attention. In the past as also today, the development of chi is how martial artists have been able to perform physically impossible feats. These include breaking huge blocks of ice or stone, withstanding blows of tremendous power on their person without any injury, generating terrifying power and speed with no apparent effort, and much more!

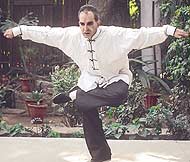

The cool, crisp winter air had all the early morning walkers relaxed and invigorated in a Delhi park. A group practicing yogasanas and some dozen-odd members of a laughter club also felt recharged. In another corner of the park, a group of youngsters were practicing their katas with seemingly boundless energy. Each group was in the park for individual goals, but all were doing one thing in common: boosting their chi. All life in the cosmos is animated by chi, which is a 'life-force' or 'vital energy' that is said to be the power that governs the universal power. Says martial arts exponent Rashid Ansari: 'Chi (pronounced 'qi') is the Chinese word for life-force or cosmic energy. The Japanese call it 'ki', we Indians call it 'prana' and 'kundalini', the Apache 'diyin' and the pygmies 'mana'. Chi is the animating power that flows through all living things. A living person is filled with it; a dead person has none. It is also the life energy one senses in nature, in the cosmos around us. It is this indwelling force that manifests as the feel of a direction or a pattern frozen within an instant. Hence, in the East and specifically in the martial arts, physical action and the indwelling life force cannot be disassociated.' Ansari claims that while all living beings have chi, it is the cultivation, expansion, harnessing and use of chi in martial arts that merits attention. In the past as also today, the development of chi is how martial artists have been able to perform physically impossible feats. These include breaking huge blocks of ice or stone, withstanding blows of tremendous power on their person without any injury, generating terrifying power and speed with no apparent effort, and much more!  It was the Chinese who developed various 'chi kong'systems to generate chi and harness its Kong (benefit or achievement)for health and well-being. The Chinese believe there are six different kinds of chi in the body: Gu chi (grain chi) that generates the body's energy Kong chi (air in the lungs) that enkindles energy Zan chi (between all organs) that is the body's original energy Wei chi (guarding energy) occupies the skin surface Xie chi (blood chi) that maintains body temperature Jin chi (sperm or egg producing chi) that is reproductive energy In India, yoga is the most popular method of raising and regulating one's prana or chi. In the Far East, martial arts practice was popular for raising chi. Martial artists mainly train in Zan chi and Xie chi. But all the other kinds of chi also benefit in the practice of the martial arts or chi Kong Ansari asserts that near-miraculous feats are possible by cultivating chi. 'This is through proper, disciplined, regulated practice of chi Kong methods. There are a whole series of breathing, meditative postures, movements and visualizations for specifically cultivating chi. Ranging from simple sets of just being aware of one's chi to the more complex ones through which one can project the chi outwards. This life-force or chi is a blending of mind-body power and a mixture of polarities, the yin-yang.' The Chinese character for yin-yang has two elements. On top is a square representing a container and underneath are four strokes rising upwards, representing fire. Taken together, the image is that of a container of air placed over fire. As the fire rises, the water remains water yet a transformation takes place, says Ansari. Bubbles burst through the surface of water and a vapor rises upwards and outwards. This can be called chi. When chi is balanced, only then is it possible to harness it. Dynamic chi Kong (moving) and passive chi Kong (still) are to be practiced together. Yang and yin chi reside in the sinews and the marrow and can form a protective sheath for the body. Chi is also the basis of Chinese healing systems. 'All martial arts work on the cultivation of chi, but some more so than others,' says Ansari. 'Chi Kong, t'ai chi ch'uan, pa kua, hsing i, aikido, kenjutsu/kendo and kyodo work on the cultivation of chi from the very beginning, whereas others may work their way in from the outside.' The area just below the navel tan tien in Chinese and hara in Japanese is called the 'sea of chi'. Cultivating chi is not just a technique but a 'practice', meaning that it is life long, ranging from simple concepts to the completely esoteric. The Chinese cultivated chi through arts like dragon kung fu, ch'i kung, and t'ai chi. The power of chi lies at the root of all martial arts and meditative practices. Taoist internal martial arts like t'ai chi, hsing-i and pakua teach practitioners how to harness chi through martial arts. For this, one had to follow the way of the Tao. These arts were taught in Buddhist monasteries. But not everyone was privy to them. Nor could one pay and learn. They could only be acquired by the desire to learn, the will to discipline one's self and fervent devotion to practice. The benchmarks were pegged so high that the Chinese considered the master to be a disciple of the way of the tiger and the sign of the dragon. Learners had to start with the most difficult and menial tasks. Over the first few years, their abilities and temperament were severely tested. If they were able to win the confidence of the monks, only then were they allowed to learn 'kung fu'a generic term for martial arts. The kung fu student trained the mind and body to work in close coordination. He would be taught the basic steps and prearranged forms simulating multiple attacks. He then advanced to complex steps, simultaneously learning Taoism. This stage complete, one became a disciple who was taught the higher secrets of the arts and philosophies. Movements were now perfected to coincide with one's breathing. And the mind would meld into the realm of meditation termed 'mindlessness'. It was now that the student really learnt to harness chi so that even a man of small stature could break bricks with his bare hands or sense movement in a dark room. Chinese systems such as t'ai chi consist of actions controlled by chi. Such arts are smooth and fluid. Says t'ai chi practitioner Mala Shukla: 'Healing through movement has been used in ancient China for over 3,000 years and t'ai chi is just one of the branches that has survived. It was also known as 'shadow boxing' or 'moving meditation'. The movements in this pattern are so simple you wonder if they are of any benefit at all!'

It was the Chinese who developed various 'chi kong'systems to generate chi and harness its Kong (benefit or achievement)for health and well-being. The Chinese believe there are six different kinds of chi in the body: Gu chi (grain chi) that generates the body's energy Kong chi (air in the lungs) that enkindles energy Zan chi (between all organs) that is the body's original energy Wei chi (guarding energy) occupies the skin surface Xie chi (blood chi) that maintains body temperature Jin chi (sperm or egg producing chi) that is reproductive energy In India, yoga is the most popular method of raising and regulating one's prana or chi. In the Far East, martial arts practice was popular for raising chi. Martial artists mainly train in Zan chi and Xie chi. But all the other kinds of chi also benefit in the practice of the martial arts or chi Kong Ansari asserts that near-miraculous feats are possible by cultivating chi. 'This is through proper, disciplined, regulated practice of chi Kong methods. There are a whole series of breathing, meditative postures, movements and visualizations for specifically cultivating chi. Ranging from simple sets of just being aware of one's chi to the more complex ones through which one can project the chi outwards. This life-force or chi is a blending of mind-body power and a mixture of polarities, the yin-yang.' The Chinese character for yin-yang has two elements. On top is a square representing a container and underneath are four strokes rising upwards, representing fire. Taken together, the image is that of a container of air placed over fire. As the fire rises, the water remains water yet a transformation takes place, says Ansari. Bubbles burst through the surface of water and a vapor rises upwards and outwards. This can be called chi. When chi is balanced, only then is it possible to harness it. Dynamic chi Kong (moving) and passive chi Kong (still) are to be practiced together. Yang and yin chi reside in the sinews and the marrow and can form a protective sheath for the body. Chi is also the basis of Chinese healing systems. 'All martial arts work on the cultivation of chi, but some more so than others,' says Ansari. 'Chi Kong, t'ai chi ch'uan, pa kua, hsing i, aikido, kenjutsu/kendo and kyodo work on the cultivation of chi from the very beginning, whereas others may work their way in from the outside.' The area just below the navel tan tien in Chinese and hara in Japanese is called the 'sea of chi'. Cultivating chi is not just a technique but a 'practice', meaning that it is life long, ranging from simple concepts to the completely esoteric. The Chinese cultivated chi through arts like dragon kung fu, ch'i kung, and t'ai chi. The power of chi lies at the root of all martial arts and meditative practices. Taoist internal martial arts like t'ai chi, hsing-i and pakua teach practitioners how to harness chi through martial arts. For this, one had to follow the way of the Tao. These arts were taught in Buddhist monasteries. But not everyone was privy to them. Nor could one pay and learn. They could only be acquired by the desire to learn, the will to discipline one's self and fervent devotion to practice. The benchmarks were pegged so high that the Chinese considered the master to be a disciple of the way of the tiger and the sign of the dragon. Learners had to start with the most difficult and menial tasks. Over the first few years, their abilities and temperament were severely tested. If they were able to win the confidence of the monks, only then were they allowed to learn 'kung fu'a generic term for martial arts. The kung fu student trained the mind and body to work in close coordination. He would be taught the basic steps and prearranged forms simulating multiple attacks. He then advanced to complex steps, simultaneously learning Taoism. This stage complete, one became a disciple who was taught the higher secrets of the arts and philosophies. Movements were now perfected to coincide with one's breathing. And the mind would meld into the realm of meditation termed 'mindlessness'. It was now that the student really learnt to harness chi so that even a man of small stature could break bricks with his bare hands or sense movement in a dark room. Chinese systems such as t'ai chi consist of actions controlled by chi. Such arts are smooth and fluid. Says t'ai chi practitioner Mala Shukla: 'Healing through movement has been used in ancient China for over 3,000 years and t'ai chi is just one of the branches that has survived. It was also known as 'shadow boxing' or 'moving meditation'. The movements in this pattern are so simple you wonder if they are of any benefit at all!'

ROOTS OF THE TAO

The origins of t'ai chi are linked with Taoism. In the sixth century BC, the founder of Taoism, Lao Tsu wrote in Tao Te Ching: Stiff and unbending is the principle of death. Gentle and yielding is the principle of life. Thus an army without flexibility never wins a battle. A tree that is unbending is easily broken. The hard and strong will fall. The soft and weak will overcome. T'ai chi is said to 'nourish the body and calm the spirit'. In this system, one moves slowly, continuously, without strain, through a varied sequence of contrasting forms. As it demands no physical strength, it is good for the young and old, male and female. It is attributed to Taoist priest and philosopher Chang San-Feng of the Sung Dynasty (11th century). Reveals Rashid Ansari: 'T'ai chi literally means 'the grand ultimate fist' or 'the grand nothing'. Its roots and philosophy lie in I Ching, The Book of Change.'' T'ai chi believes that all life comprises the constant interplay of yin (ida in Indian philosophy) the passive, feminine part and yang (pingala) the active, masculine principle. Unlike other martial arts, in t'ai chi the body movements do not strain the muscles. According to Mala, it is totally non-aggressive, in line with Taoist principles of following 'the way of nature'. T'ai chi increases concentration, discipline and will power. The sessions have a tranquilizing influence, imparting a personal sense of balance. In today's stressful world, t'ai chi can help one relax. Mala says that its benefits are too vast to be outlined: 'T'ai chi balances your yin and yang. The practice gives all internal organs a good massage. The movements promote the flow of chi, enhancing blood circulation and releasing stiffness in the joints. Each posture is designed to stimulate the center of gravity, developing a sense of balance in every aspect of life.' Continues Mala: 'T'ai chi is a philosophy that encompasses medical practice, ordinary exercise, martial art, psychology and spiritual practice all rolled into one. It is subtler than yoga. Prolonged practice brings you to a state of self-discovery.' T'ai chi is the proper flow of chi. The power of chi can be comprehended if we consider the examples of wind and water. A gentle breeze simply rustles the leaves, yet, can even the mighty oak withstand the power of a whirlwind? And a single drop of water is soft, gentle, harmless, yet what can withstand the ferocity of a tsunami? Likewise, even a gentle being can multiply his or her energies many times over by tapping the power of chi. All this would be used in the pursuit of peace. A martial artist never attacks anyone; nor does s/he use lethal defenses in most situations. Even when attacked, a practitioner doesn't counterattack, choosing instead to parry. If the opponent is skilled and determined to do harm, a stronger response may be used, such as a joint lock or a knockout. A fatal counterattack would be the last resort. The more violent the attack, the more devastating the return of an attack.  A long time after these exercises were in vogue, the Indian monk Bodhidharma (sixth century AD) visited China, settling down in the Shaolin Monastery. Bodhidharma called Ta Mo by the Chinese taught Zen Buddhism and meditation. He noticed that the Shaolin monks were frail, unaware of the importance of physical fitness in attaining nirvana. He put the monks through the paces with his 18-Form Lohan Exercise which he said 'would transform the body into a strong abode, to provide the soul with a dwelling place'. Bodhidharma's exercises were modified from yoga. These exercises would go to form Shaolin kung fu in the years to come. With the Shaolin temple being located in a secluded area, bandits and wild animals were sometimes a problem. So what began as exercises to keep fit and enhance chi gradually transformed into martial exercises and would be later codified into a self-defense system.

A long time after these exercises were in vogue, the Indian monk Bodhidharma (sixth century AD) visited China, settling down in the Shaolin Monastery. Bodhidharma called Ta Mo by the Chinese taught Zen Buddhism and meditation. He noticed that the Shaolin monks were frail, unaware of the importance of physical fitness in attaining nirvana. He put the monks through the paces with his 18-Form Lohan Exercise which he said 'would transform the body into a strong abode, to provide the soul with a dwelling place'. Bodhidharma's exercises were modified from yoga. These exercises would go to form Shaolin kung fu in the years to come. With the Shaolin temple being located in a secluded area, bandits and wild animals were sometimes a problem. So what began as exercises to keep fit and enhance chi gradually transformed into martial exercises and would be later codified into a self-defense system.

THE INFLUENCE OF ZEN

While Taoism heavily influenced the martial arts in China, Zen Buddhism left a heavy imprint on all forms of combat in Japan. Archery was not practiced solely to hit the target. The swordsman does not draw his sword simply to subdue his opponent. The taekwondo master does not practice to break a brick. All of these are just the medium to go beyond, to free the mind and to bring it in contact with the Ultimate Reality. Mastery of an art is not technical; one has to transcend technique. The art has to become 'artless'; the form has to become 'formless'. There is no duality between the outside and the inside; they become one. In the case of kyudo or archery, there is no target and no archer, only one reality. The archer ceases to be conscious of him as the one who is engaged in hitting the bull's eye that confronts him. This state of unconsciousness is realized only when, completely empty and rid of the self, he becomes one with the perfecting of his technical skills and goes beyond it. A famous Zen archer once said: 'I'm afraid I don't understand anything any more and have given up trying to understand! Is it I who draws the bow, or is it the bow that draws me into the state of highest tension? Do I hit the goal or does the goal hit me? Is it spiritual when seen by the eyes of the body and corporeal when seen by the eyes of the spirit or both or neither? Bow, arrow, goal and ego all melt into one another, so that I can no longer separate them. And even the need to separate has gone. For as soon as I take the bow and shoot, everything becomes so clear and straightforward and simple' Thomas Hoover says in his book, Zen Culture: 'The first Zen archery lesson is proper breath control, which requires techniques learned from meditation. Proper breathing conditions the mind and is essential in developing a quiet mind, a restful spirit, and full concentration.  'Thus it was that the martial arts of Japan were the first to benefit from Zen precepts, a fact as ironic as it is astounding. Yet meditation and combat are akin in that both require rigorous self-discipline and the denial of the mind's overt functions.' Zen Buddhism's biggest influence on martial artists was that it made them fearless, even in the face of death. In Zen Buddhism: Selected Writings of D.T. Suzuki, he says: 'If a soldier came to a master saying, 'I have to go through at present with the most critical event of life; what shall I do?' the master would roar, 'Go straight ahead, and no looking back!' This was how in feudal Japan soldiers were trained by Zen masters.' In such a backdrop, even the art of swordsmanship kenjutsu and iaijutsu had spiritual connotations, despite the seeming paradox. Although both are components of Japanese bujutsu (arts of war), the sword in both martial arts is considered to be an instrument that annihilates things that stand in the way of peace. The sword is also identified with the annihilation of the ego or self. Iaijutsu came into its own around 1868, during the Meiji era, when the public wearing of swords was banned. The art of swordsmanship was more than just the practical act of bringing the sword into active combat. It was necessary for the swordsman to develop his mind as well as spirit and each was considered incomplete without the other. Swordsmanship dedicated to spiritual aims was a means by which the samurai advanced his study of 'the Way'. In this spiritual, mystical study, the technical part was thought to be secondary to the inner quest. It is in this respect that the way of the sword and Zen happen to be similar�both have the same goal, conquest of the ego. Both view life and death as the same and the swordsman trains to achieve a state of seishi o chosetsu suru, transcending thoughts about life and death. The ancient system where mind and technique merge applies even today. The father of modern karate, master Gichin Funakoshi has said that 'mind and technique become one in true karate'. The Karateka strives to make physical techniques a pure expression of the mind's intention and improves concentration by understanding the essence of physical techniques. By honing one's technique, the practitioner is simultaneously honing his own attitude or spirit. For example, by eliminating indecisive moments during sparring, one learns to eliminate indecisiveness in daily life. This is how karate becomes a way of life, thereby making the practitioner strong, stable and peaceful. Says Tsutomu Ohshima, Shihan (chief instructor) of Shotokan Karate of the USA: 'We must be strong enough to express our true minds to any opponent, anytime, in any circumstance. We must be calm enough to express ourselves humbly.'

'Thus it was that the martial arts of Japan were the first to benefit from Zen precepts, a fact as ironic as it is astounding. Yet meditation and combat are akin in that both require rigorous self-discipline and the denial of the mind's overt functions.' Zen Buddhism's biggest influence on martial artists was that it made them fearless, even in the face of death. In Zen Buddhism: Selected Writings of D.T. Suzuki, he says: 'If a soldier came to a master saying, 'I have to go through at present with the most critical event of life; what shall I do?' the master would roar, 'Go straight ahead, and no looking back!' This was how in feudal Japan soldiers were trained by Zen masters.' In such a backdrop, even the art of swordsmanship kenjutsu and iaijutsu had spiritual connotations, despite the seeming paradox. Although both are components of Japanese bujutsu (arts of war), the sword in both martial arts is considered to be an instrument that annihilates things that stand in the way of peace. The sword is also identified with the annihilation of the ego or self. Iaijutsu came into its own around 1868, during the Meiji era, when the public wearing of swords was banned. The art of swordsmanship was more than just the practical act of bringing the sword into active combat. It was necessary for the swordsman to develop his mind as well as spirit and each was considered incomplete without the other. Swordsmanship dedicated to spiritual aims was a means by which the samurai advanced his study of 'the Way'. In this spiritual, mystical study, the technical part was thought to be secondary to the inner quest. It is in this respect that the way of the sword and Zen happen to be similar�both have the same goal, conquest of the ego. Both view life and death as the same and the swordsman trains to achieve a state of seishi o chosetsu suru, transcending thoughts about life and death. The ancient system where mind and technique merge applies even today. The father of modern karate, master Gichin Funakoshi has said that 'mind and technique become one in true karate'. The Karateka strives to make physical techniques a pure expression of the mind's intention and improves concentration by understanding the essence of physical techniques. By honing one's technique, the practitioner is simultaneously honing his own attitude or spirit. For example, by eliminating indecisive moments during sparring, one learns to eliminate indecisiveness in daily life. This is how karate becomes a way of life, thereby making the practitioner strong, stable and peaceful. Says Tsutomu Ohshima, Shihan (chief instructor) of Shotokan Karate of the USA: 'We must be strong enough to express our true minds to any opponent, anytime, in any circumstance. We must be calm enough to express ourselves humbly.'

MARTIAL ARTS TECHNIQUES

A martial art involving a variety of techniques, Karate includes blocks, strikes, evasions, throws and joint manipulations. The practice is divided into three parts: kihon (basics), kata (forms), and kumite (sparring). The word 'karate' is a combination of two Japanese characters: kara, meaning 'empty', and te, denoting 'hand'. This Japanese martial art goes back 1,400 years and is credited to the monk Bodhidharma. Japanese legend says that when Bodhidharma took Buddhism to China, his spiritual and physical teaching methods were so rigorous, many disciples collapsed in exhaustion. To build up their stamina, he devised a training system, recorded in his book, Ekkin-Kyo, now considered the world's first book on karate. Another Japanese martial art perfected in modern times is aikido. Developed by Morihei Ueshiba in the late 1800s, it involves throws and joint locks derived from jujitsu and other throws and techniques from Kenjutsu, combining these with body movements from sword and spear fighting. If followed religiously, practitioners will discover whatever they're looking for self-defense techniques, spiritual enlightenment, physical health or peace of mind. Ueshiba stressed the moral and spiritual aspects of aikido, accentuating the development of harmony and peace. Aikido translates as the 'way of harmony of the spirit'. The secret of aikido, masters claim, is to become one with the universe and this is achieved through the cultivation of chi. The philosophical core includes a commitment to peaceful resolution of conflict whenever possible, and to self-improvement through aikido training. Martial arts can even help women in their daily lives. Women become more confident physically and mentally as the training increases their level of awareness. For instance, if a large man accosts a woman who has received only a fortnight's training, she might still not be in a position to subdue him. But she can quickly take evasive action. 'Jujitsu and wing chun are practical, easy-to-use systems whose simple movements can be executed by women,' reveals Ansari. The confidence that knowledge of such techniques imparts helps women deal better with day-to-day stress. In Korea the practice of martial arts dates back to 50 BC, then known as taek kyon. Evidence of this early practice exists in tombs, where wall paintings depict two men in a fighting stance. Taekwondo utilizes fast, explosive movements and lethal kicks. The name was adopted in the mid-1950s, influenced by the ancient Korean nomenclature, taek kyon. In Chinese, tae literally means 'foot'. Kwon implies 'striking with the fist'. Do is 'the way' or 'the correct path'. Taekwondo thereby denotes 'the way of the hand and foot'. There are scores of other martial arts such as hung gar, hapkido, kendo, escrima, Thai boxing, kenjutsu, aikijutsu.

INDIGENOUS SYSTEMS

India too has numerous martial arts, kalaripayattu of Kerala being the most well-known among them. The highest stage of kalaripayattu is marmaadi, based on the knowledge of the body's marma (vital) points. The human body is believed to have 26 meridians through which prana or chi flows. Marma points, over a hundred, are located on these meridians. When pressure is applied on a marma point, the prana flow alters. The key lies in the degree of force used. A forceful blow on a marma point might lead to paralysis or even death. Less pressure applied in a particular way on the same point will induce healing by correcting the prana flow, as done in marma chikitsa, practiced in Kerala. The Indian state of Tamil Nadu's very own martial art form is the silambam, where a staff and fencing techniques are used for fighting. The martial art of the Indian state Punjab is gatka where swords and other weapons are used. The cheibigad-ga is practiced in another Indian state, Manipur, in which the sword and shield are used. Unlike kalaripayattu, here the sword is smaller but sharper. Thang-ta and sarit-sarak are the other Manipuri martial arts. Here too, the sword and shield are used. These arts also teach hand fighting against armed and unarmed opponents. Thang-ta also incorporates tantric practices. Rashid Ansari asserts there's more to martial arts than fighting and breaking bricks or blocks of ice. 'There's the mystical aspect a spiritual journey. It can be a great means of self-discovery on two counts if it is taught correctly and you learn it sincerely, because then it forces you to look within yourself; and if working with the technical aspects is a direct reflection of the struggle of coping with life.' The basic philosophy behind martial arts is defensive, not offensive. This has been lost sight of in today's competitive times. In the old days, the only competition was with one's own ego. You were taught how to transcend your ego and tap the chi. 'Meditation in martial arts can mean practicing with total absorption. You then don't really think of yourself as 'I' but as part of a composite whole,' says Ansari. One important question for those seeking to practice martial arts is: Which is the best system? Well, there is no best or second-best system. Depending on various parameters, a system that suits one individual may not suit another. Each aspiring practitioner must decide what s/he is looking for and choose accordingly. Whatever system you choose, there will be results to show.

To read more such articles on personal growth, inspirations and positivity, subscribe to our digital magazine at subscribe here

Life Positive follows a stringent review publishing mechanism. Every review received undergoes -

- 1. A mobile number and email ID verification check

- 2. Analysis by our seeker happiness team to double check for authenticity

- 3. Cross-checking, if required, by speaking to the seeker posting the review

Only after we're satisfied about the authenticity of a review is it allowed to go live on our website

Our award winning customer care team is available from 9 a.m to 9 p.m everyday

The Life Positive seal of trust implies:-

-

Standards guarantee:

All our healers and therapists undergo training and/or certification from authorized bodies before becoming professionals. They have a minimum professional experience of one year

-

Genuineness guarantee:

All our healers and therapists are genuinely passionate about doing service. They do their very best to help seekers (patients) live better lives.

-

Payment security:

All payments made to our healers are secure up to the point wherein if any session is paid for, it will be honoured dutifully and delivered promptly

-

Anonymity guarantee:

Every seekers (patients) details will always remain 100% confidential and will never be disclosed