- Home

- Archive -Dec 1998

- Let's play scho. . .

Let's play school

- In :

- Others

By Deepti Priya Mehrotra

December 1998

You could put your children in a school that hammers them into assembly-line products. Or you could choose an education that nurtures your children into creative, sensitive individuals. First of a two-part report from the leading alternative schools and their underlying philosophy

1965. All of four years old, I’m bursting with excitement as I wear my new uniform-red checked skirt, starched white blouse, striped tie. I’ve been longing for this day, green with envy as I see my sister go to the ‘bada ( big ) school’ every morning. Already I have tasted school-an experimental ‘model school‘ in which I’ve played on swings and slides, built blocks, crayoned and painted to my heart’s content. I imagine ‘bada school’ to be a bigger, brighter version of this.

The day, however, turns out to be probably the worst one of my life. I have to sit at a desk, one of a row of small uniformed human beings. Uneasy, required to be quiet. I feel faceless, nameless. The teacher looks at us with lethargy and disinterest. I am chilled by the cold, unfriendly atmosphere.

Slowly, I grow used to my ‘bada school’. Survival instincts to the fore, I gravitate towards another teacher—bright, smiling—and sit in her class, refusing to budge. At recess, I seek refuge with my sister. As years roll by, I even learn to love my school. It has some wonderful teachers with strong values. In Presentation Convent, and later in Carmel Convent, in New Delhi, India, I learn the meaning of commitment, hard work and responsibility.…But I remember wondering, often longing-for something different. What, I know not…

|

1993. Back to school! As parents seeking admission for our child, we need to pick up the prospectus, fill in forms, seek information, even go through long tests. Recalling with horror the cold anonymity of my early school life, I sought a friendly, warm atmosphere, where my daughter would receive individual attention. We found it, in Mirambika—a rare school amid the hustle-bustle of New Delhi, India—a school that tries to enable each child to grow at a unique, inwardly-motivated pace, nurtured with loving attention.

Gradually, I was introduced to the school’s philosophy—the thoughts of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother ( cofounder of Aurobindo Ashram ). ‘The aim of education’, said Sri Aurobindo, ‘is to help the child to develop his intellectual, aesthetic, emotional, moral, spiritual being and his communal life and impulses out of his own temperament.’

A school like Mirambika helps unfold unknown dimensions within the child. Parents, too, look and learn: from the place, from diyas ( the collective term for teachers: didis or elder sisters and bhaiyas or elder brothers ), from their own children.

‘It’s the kind of school I wish I had been to’—more than one parent has felt this sentiment rustle through the mind while walking down the ‘Sunlit Path’ to collect the kids. Here, squirrels play hide and seek, parrots squawk and chatter. In spring and early summer, the hardened golden-brown pods of the gulmohar trees beat a rhythm as they hit against one another. More than one child has stopped to gaze at these music-makers or pick one fallen on the ground.

Here, you can find tranquility, simplicity and joy. As my daughter hops her way from one year to the next, one group to the next, she gathers in the colors, soaks them deep within her, expresses and lives the spectrum from one mood to the next. The classes are not numbered here. Rather, they have names like Red Group, Blue Group, and later, Progress Group, Sincerity Group, Gratitude Group.

Not that all is perfect here. Alternative schooling has its share of problems too.

Like most parents I know, I fret, am confused, sometimes anxious. All around, children write and read by the age of five. But in Mirambika, there seems no end to free play, sports, drama, insect-collection, flower-growing, tree-climbing, face-painting and papier-mâché modeling. Formal reading and writing skills settle in only by the age of seven or eight. Sometimes, I wonder if the children will lose out on formal skills. In the long run, would a ‘normal’ school be better?

From my school days, I remember feeling fearful, lost in anonymity, painfully shy. On the other hand, I learnt the three R’s, and received a training in academic skills that helped develop professional competence and confidence.

Is it possible to have both—academic skills as well as a free and happy childhood?

I speak to parents whose children study in conventional schools. Many are dissatisfied, because their children have to cope with too much study, too little play. Parents worry when they find their children losing their appetite and zest for life.

So, is there a clear option?

For every thousand mainstream schools in the country today, there is perhaps just one that poses any kind of real alternative.

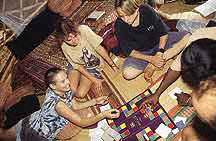

All alternative schools are guided by a clear philosophy of education and life. They are small, with a limited number of children in each class. In the alternative schools I visit, I find a warm, relaxed and creative atmosphere.

CREATING ALTERNATIVES

Says a disturbed Nirmala Diaz, 43, who works for an ad agency in Hyderabad, the capital of the southern Indian state of Andhra Pradesh : ‘When I began looking for a school for my son, I found schools treat children as raw material, to be hammered into shape. I was shocked.’ So Nirmala began searching for alternatives, and is now involved in running Shloka, started in Hyderabad, India, last year.

When I visit Shloka, I find the teachers singing, children dancing in rhythm, stamping their feet and clapping as they play number games. The classrooms are bright, curtains in soft pastel shades, surroundings green, with huge rocks upon which children climb and play. Class-time, for the little ones, means story-time. The school believes that children up to the age of seven live in a world of fantasy. Undue pressures harm the children irretrievably.

The Education Renaissance Trust, which runs Shloka, is guided by the thoughts of Rudolf Steiner, German sage and mystic. Steiner, whose philosophy has been influential across the world, set up his first school in 1919 for the children of workers in the Waldorf cigarette factory at Stuttgart, Germany. Today there are some 700 independently run Steiner schools in the world, following what is called the Waldorf model of education.

In his first school, Steiner closely observed the needs of children at different stages of growth. Up to the age of seven, the child is a creature of will; from age seven to 14, feeling predominates; from 14 to 21, the thinking capacity is the strongest. Education, in Steiner schools, takes its cue from this natural pattern of the child’s development.

Anandhi, 36, left her job in a mainstream school to teach in Shloka. ‘Childhood years,’ she notes, ‘are vital to our total existence. Overloading children early, with too much memory-oriented learning and formal writing, can cripple a child’s sense of wonder.’

|

Tina Bruinsma, 46, specialist in Steiner methods, contends that learning is as natural to a child as flying to a bird. It comes at the right time if the right stimuli are provided. Too-early imposition of formal skills will harden a child’s soul, she says. ‘Steiner learnt so much from India,’ she reveals. ‘He drew inspiration from your sacred books. It is wonderful that his ideas should come back to India.’

Today, it is little Medha’s seventh birthday, so the children sing a special song for her. She is an alert, enthusiastic child. When she came to Shloka, Medha had withdrawn into a world of her own, unable to cope with the stress of a normal school. In Shloka, she has flowered.

THE ORIGINS

In India, traditional places of learning such as gurukuls and madarsas, and small village schools provided a grounded education over the centuries. Gradually, these were replaced by schools based on a derivative model. Borrowed from the already-industrialized Western world, the new English-education schools were set up to produce standardized individuals who would fit into industrial society and its values. This is now the common pattern followed in all Indian schools—public, private, or government.

The alternative education movement began as a creative reaction to this mass-production approach that dominated education across the world by the beginning of the 20th century. This movement believes that each child is special, and deserves special attention. The whole person must be addressed, not fragmented parts. Fantasy and imagination should be allowed to ripen in a child, and independent thinking filled with idealism in the adolescent. As these children grow into adulthood they will create new ways and visions not only for themselves, but for the entire human race.

Maria Montessori, who worked with orphaned and handicapped children in Italy, conceived of education as a response to the child’s initiatives. She developed very precise teaching materials, which, by now, have become popular all over the globe.

Nobel Laureate for literature, Rabindranath Tagore pointed out limitations in the conventional schools set up in India by colonial authorities through his writings Shikshar Her Fer (1893) and Shikshar Bahan (1915). In Shikshar Bikiran (1933), he favored the father of the Indian nation, Mahatma Gandhi’s call for noncooperation with contemporary education, saying: ‘There are times when it may be more educative to boycott schools rather than joining them.’ This thought was echoed many years later, in 1983, in Ivan Illich‘s Deschooling Society.

Tagore set up his own alternative to the prevailing system: Vishva Bharati, in Santiniketan, located in the eastern Indian state of West Bengal. Classes here were—and still are—held in the lap of nature.

Gandhi developed Nai Taleem or New Education. In Gandhian schools, a few hours a day are devoted to reading and writing, and another few to the performance of ‘bread labor’—crafts-work, agriculture, cooking, cleaning. ‘Educating children,’ he said, ‘should normally be the easiest of things; but somehow it has become, or been made, the most difficult.’

|

Gujrat-based Gijubhai Bhadeka set up Dakshinamurti Bhavan, a school in Gujarat, India. Gijubhai worked with children in the village context, teaching them history, geography and other subjects in a way that would appeal and be relevant. His book Divasvapna is a fascinating account of how an inspired teacher can introduce meaningful education even in an ordinary school.

For Jiddu Krishnamurti , the real issue in education was ‘to see that when the child leaves the school, he is well established in goodness, both outwardly and inwardly’. The child is to be open, aware and fearless.

Sri Aurobindo and the Mother developed their idea of education for the whole person. The Mother worked closely with children, evolving a philosophy of ‘Free Progress’—each child developing and flowering in an absolutely spontaneous, inwardly centered and self-directed, process.

FITTING IN?

Parents often wonder if alternative education will mar their children’s capability to adjust to the ‘real’ world-taking up jobs, coping with the pressures of life.

Says Richa Grover, a housewife: ‘Though I was keen on alternative education for my children, I felt they might have trouble coping with the mainstream. So I decided against it.’

Marianne, a teacher, says her children initially studied in Mirambika in New Delhi, India, and then opted for another, bigger school. Says she: ‘At Mirambika, my children learnt to trust people and the world. Later, they opted for a mainstream school, because they wanted to meet the challenge. They are doing fine.’

What of the children who stay on at alternative schools? Says Shailesh Shirali, Principal of Rishi Valley School (run by the Krishnamurti Foundation), India: ‘Our children are in a protected environment. As they prepare to leave class 12 they often share a worry that in college nobody will care, whatever they may do.’ At the same time, Shirali finds that ‘a strength has been built up which helps the children resist pressures to conform to values they do not believe in’.

Shirali shows me a letter he has just received from an ex-student, Amitabh. Amitabh shares the news that he has got through the IAS examination, then writes that people keep asking how he gets through competitive examinations after having studied in a noncompetitive school. ‘The school taught me to compete,’ he muses, ‘not with others, but with my own self. I learnt to pursue excellence.’

Says Dilip Bhai, mathematics and physics teacher at the Sri Aurobindo International Center for Education (SAICE), Pondicherry, India: ‘Alternative education scores better because today what counts is not how much you know, but how far you are able to keep learning. The world is moving very fast. To cope, the child has to be able to adjust. Our education encourages an attitude of self-confidence, learning and self-study.’

Alternative education seems to nurture latent capabilities and inculcate love for learning. Those with such a background are usually more versatile, and capable of seeing the whole picture. They are better fitted to take decisions, introduce changes. They manage to cope and do surprisingly well in the outer world.

Says Kabir Jaitirtha, ex-teacher at the Valley School, Bangalore, capital of the southern Indian state of Karnataka, run by Krishnamurti Foundation, and cofounder of Center For Learning, Bangalore: ‘Our old students are doing well. They are designers, writers, mathematicians. One is pursuing ceramics full-time, another weaving. Each has an individual course, we help them navigate it.’

Promesse Jauhar, who has taught for 20-odd years at SAICE, says: ‘Anyone can buy a degree. At our school, there are no examinations or degrees. If they decide, students sit for entrance examinations in other institutions. Usually they do well. Many of our students have gone on to study at Jawaharlal Nehru University, India, Indian Institute of Technology, Hyderabad University, India, Pondicherry University, India.’

THE NEXT MILLENNIUM

‘A school makes a breakthrough if it creates a learning environment to bring the future humanity into being,’ says 37-year-old Partho, principal of Mirambika. He is confident about the future of alternative education.

Krishnamurti’s questions are direct and piercing: ‘Why are we so sure that neither we nor the coming generation, through the right kind of education, can bring about a fundamental alteration in human relationship? We have never tried it… we accept things as they are and encourage the child to fit into the present society… But can such conformity to present values, which leads to war and starvation, be called education?’

Few relevant studies have been conducted in India on the results of different kinds of schooling. Mainstream schools may be more in consonance with the world of today. On the other hand, alternative education may be more in consonance with the world of tomorrow.

It is for each of us to make an active choice for our children. Children who will be molded by the choices we make. It is an awesome power we hold in our hands, as adults, as teachers and as parents.

For our children will inherit the earth, and be the arbiters of tomorrow.

To read more such articles on personal growth, inspirations and positivity, subscribe to our digital magazine at subscribe here

Life Positive follows a stringent review publishing mechanism. Every review received undergoes -

- 1. A mobile number and email ID verification check

- 2. Analysis by our seeker happiness team to double check for authenticity

- 3. Cross-checking, if required, by speaking to the seeker posting the review

Only after we're satisfied about the authenticity of a review is it allowed to go live on our website

Our award winning customer care team is available from 9 a.m to 9 p.m everyday

The Life Positive seal of trust implies:-

-

Standards guarantee:

All our healers and therapists undergo training and/or certification from authorized bodies before becoming professionals. They have a minimum professional experience of one year

-

Genuineness guarantee:

All our healers and therapists are genuinely passionate about doing service. They do their very best to help seekers (patients) live better lives.

-

Payment security:

All payments made to our healers are secure up to the point wherein if any session is paid for, it will be honoured dutifully and delivered promptly

-

Anonymity guarantee:

Every seekers (patients) details will always remain 100% confidential and will never be disclosed

Alternative schools have a small number of studentsChildren are allowed to learn the basic skills of reading and writing at their own pace

Such schools may or may not subscribe to the national examination system. Learning is pursued for the sake of knowledge and building character

There is an inherent spirit of cooperation with an internal discipline. The uniqueness of each child is nurtured

There is little or no internal hierarchy in alternative schools. The ambiance is essentially fluid and informal

Nandita’s diary

The eight-year-old accompanied her mother, Deepti, to various schools

31.8.98 : I am at the Aurobindo ashram, it is wonderful. It is in Pondycherry.

1.9.98 : I saw a red and black centipede. There were two of them. I saw them at the Shri Aurobindo school. I climbed a big gulmohur tree, and saved some ants almost drowned in a little water in a little hole in the tree.

2.9.98 : Today I went to Auroville. I first went to the kindergarten. It was very beautiful, all the children were very small-small they were very cute.Then we went to the New School. It had tree house classes. And little ponds. And the children were designing their school. Then we went to an uncle’s house in a school called New Creation. He had four dogs and six cats, 21 small birds in a big cage, 11 rabbits, and 18 fish in the biggest size of aquarium.

5.9.98 : Rishyvaly is very nice, in it I saw a big tree. Rishivaly has many beautiful birds. There are many cats and dogs even. And I like them all. There is a boding school in Rishivaly. And I am staying in Birds house.

6.9.98 – Today I made a new friend, her name is Shweta. I liked her and she liked me.

7.9.98 – I saw a school called RISHIVANM, there were mud room classes. The children were poor children. There were 70 children. They had made swings and slides themselves. Like we can. It was very beautiful.