- Home

- Archive -June 2010

- Saint of the gu. . .

Saint of the gutters

- In :

- Personal Growth

June 2010

By Shrikant Rao

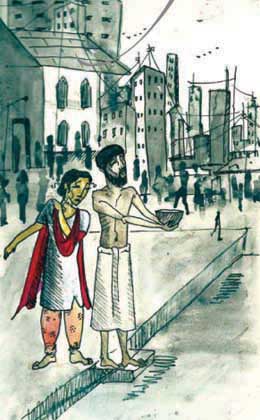

Baba Maula’s self-appointed mission is to minister unto the souls of the denizens of Mumbai’s notorious red-light areas

|

At ten in morning, Pila House is as busy as it is at any given time of the day. In this narrow nightmare of a street, handcarts, water tankers, taxis, double-decker buses, urchins, pimps, junkies and gauche looking men, begin their slow crawl past the horrendous cages and the painted faces. Maula, the 60-something dervish in his trademark discoloured lungi and a black bandana, however, is entirely at ease in this setting as he exchanges pleasantries with a madam with paan-stained teeth who is supervising cleaning operations.

It is washing day. The dim lit cages are being cleaned, the floors scrubbed and washed and the girls empty the soapy contents on to the street. The sage, who narrowly escapes a jet of dirty water, breaks into expletives. There is a titter among the girls. Madam glares at the girls and extracts a five-rupee note from within her blouse and profers it with “Baba maaf karna hai!”

Maula, now adequately mollified, tucks the note away in the folds of his lungi and makes small talk. “Is everything fine?” he enquires of no one in particular, the lilt in his Urdu of southern provenance. “Sub jhakaas hai (everything is fine) baba,” parrots the hyperactive beauty in the next cage in local street lingo, first wiggling her bottom and then performing that ultimate dare – the Indian eunuch’s version of the Mexican wave which can strike terror in the most hardened of souls. In the midst of this high voltage performance, two youngsters perched in the window of a rundown building on the opposite side of the street train their plastic binoculars.

It does not require much imagination to determine what they are hoping to discover at the other end of the toy. Clearly, the boys are in no mood to sound retreat as the local bombshell s t r ikes poses . Whi s t les and catcalls follow. “Baba, see Mallika Sherawat!” If the mendicant appears shocked, he is not showing it. Over the years that Maula has been doing the rounds of the area, he has become inured to the antics of its inhabitants. Moreover, if some of them do appear to be having fun at his expense it is not intended as disrespect, he maintains. Who doesn’t respect an emissary of God? A little mischief here and there can sometimes help lighten the load in their heart and minds. “I understand and pray for them,” says the begging saint displaying a remarkable capacity for psychology.

To the sex workers of Mumbai’s red light zone, Maula is simply one of the many holy men who bring good luck – to be read as good business, and they are not averse to passing on a part of their earnings to him. Maula for his part relishes the attention and the money that he gets during his daily perambulations across the street. He will not tell you though how much he makes in a day. “Police and tax people are not to be trusted,” he says with a pragmatism that can only be admired. If Baba is different from others of his ilk, it is mainly because he has a definite purpose in life. He sincerely believes that the Most Merciful has chosen him to minister to the spiritual needs of the dregs of society. He says that he did not take to begging to sustain himself, but in order to support his family back home in the south. There are even whispers that he did all this to see a son through engineering college. However, we will never know – the begging saint dislikes discussing personal matters.

Aeons ago, we are told, when he landed in the city, Maula tried his hand at odd jobs but gave up when he discovered that he had spiritual leanings. In later years, he realised that idle spirituality did not bring in the bucks, and that it would only allow people depending on him a Barmecide Feast. That is when he became a baba and embraced the bowl. It has not been an asy trek to sainthood for Maula, who claims to have encountered tough times.

“I have often gone hungry for days. I was harassed by the police for bribes, and by jealous beggars, who could not bear to see food and money coming my way. Very often, I ended up being robbed of whatever little belongings I had. It was all Allah’s will and he gave me the strength to surmount all my problems.” It was this experience, which made him an epitome of thrift.

When Maula is not on the move, which is rare, he lives outside a public toilet, often helping friends with his hard-earned money, but with the proviso that it is returned to him. Like a good Muslim, he does not charge interest. And though he is known to pinch pennies in order to sustain his family – it is said that he dispatches most of the money he collects to his family through his network of beggar friends – he is also generous when it comes to treating a guest, in this case yours truly. “There is after all something called hospitality. Money is very important but more important is our duty to the Most Merciful,” he says, as he offers to pay for a cup of tea. The waiter at Zulfikar, the eatery that Maula frequents, s e ems to acqui e s c e r eadi l y with that philosophy. He will not accept your offer to pay the bill. And, “Baba’s word is final,” says it all.

If Maula inspires respect among his tribe, it is mainly because of his caring nature. Forever on the move, he is known to share his meal with those who are infirm, visit sick peers and act as a counsellor for those who have fallen on evil ways. A young beggar high on cocaine gets a severe tonguelashing from the mendicant, and looks sheepish. He next proceeds to hold both his ears in a manner suggesting repentance and promises to stay free of drugs. Baba though looks thoroughly unconvinced, “What will you tell Allah on the Day of Judgment?” – the poser does seem to suggest that he takes his self-appointed role as God’s representative quite seriously.

Characteristically the beggars lined up outside the restaurant break into laughter at his ministrations. “Baba let’s go to eat,” they say breaking into a chorus. Maula pauses for a while and then shakes his head despondently, “No one understands me.”

But very soon, this seriousness gives way to cheer – as food provides the diversion. The saint will now retire to a spot outside a nearby restaurant where he will join the double row of squatting beggars for leftover food. “The food there is very good,” says the mendicant with a grin, indicating that he is not entirely averse to the simple pleasures of life. “If it is mutton it has got to be Mohammed Ali Road,” he adds with a conviction that can only come from years of gourmet living. Soon enough the altruistic side of Maula comes to the fore. After collecting the afternoon’s goodies from the restaurant, much of the fare is handed over to a stray dog prospecting for food.

As he says, “It’s all Allah’s will.”

To read more such articles on personal growth, inspirations and positivity, subscribe to our digital magazine at subscribe here

Life Positive follows a stringent review publishing mechanism. Every review received undergoes -

- 1. A mobile number and email ID verification check

- 2. Analysis by our seeker happiness team to double check for authenticity

- 3. Cross-checking, if required, by speaking to the seeker posting the review

Only after we're satisfied about the authenticity of a review is it allowed to go live on our website

Our award winning customer care team is available from 9 a.m to 9 p.m everyday

The Life Positive seal of trust implies:-

-

Standards guarantee:

All our healers and therapists undergo training and/or certification from authorized bodies before becoming professionals. They have a minimum professional experience of one year

-

Genuineness guarantee:

All our healers and therapists are genuinely passionate about doing service. They do their very best to help seekers (patients) live better lives.

-

Payment security:

All payments made to our healers are secure up to the point wherein if any session is paid for, it will be honoured dutifully and delivered promptly

-

Anonymity guarantee:

Every seekers (patients) details will always remain 100% confidential and will never be disclosed