- Home

- Archive -Apr 2018

- Sustaining the . . .

Sustaining the planet

- In :

- Personal Growth

Having consciously lived a very eco-friendly lifestyle, in India as well as abroad, Sridevi Lakshmi Kutty makes a strong case for reducing our ecological footprints in whatever way we can

Ironically, my husband and I began our journey to understand ecological sustainability and holistic living after we moved to the most consumerist and profligate society in the world—the United States of America. Moving from middle-class India in the early 2000s, we found that although the extravagance was in some ways attractive, we were strangely reluctant to join the race. This exposure to plenty was also combined with our exposure to the Narmada water struggle, the issues of the farmers, etc., which we had started exploring and comprehending. Sustainability was a political and personal struggle for us, particularly me. Suddenly the ability to buy without thinking twice was mingled with the dawning awareness about the need for restraint. I found that practising the four tenets— refuse, reduce, reuse, and recycle— is really much harder than it seems.

I am far from being a poster woman for sustainability; I struggle with many aspects of it. I love hand-woven clothes, can’t resist buying a good book, do travel by air and air-conditioned class by train, and still need to be reminded to switch off the lights. My ecological footprint is not as low as it should be; maybe I am more conscious of it as my husband manages a low footprint effortlessly. When I say that I do ‘ethical shopping’, he points out that it is an oxymoron. Now the biggest mirror to my inadequacies in this quest is our feline companion, Mooi, treading ever so lightly and joyfully, making her way through life.

One of the keys to sustainability, we learnt early on, is to pay more and buy less; anything produced sustainably and ethically will cost more. Be it food grown organically, clothes woven by hand using non-chemical dyes, or sustainable articles made without the use of plastics, they all cost more and rightly so. We realised early on in this journey that we should be prepared to buy only what we need and not go after everything that catches our eye. That’s easier said than done when things become cheap and disposable. The disposable culture has made us negligent of quality; we value quantity and low price over many other factors.

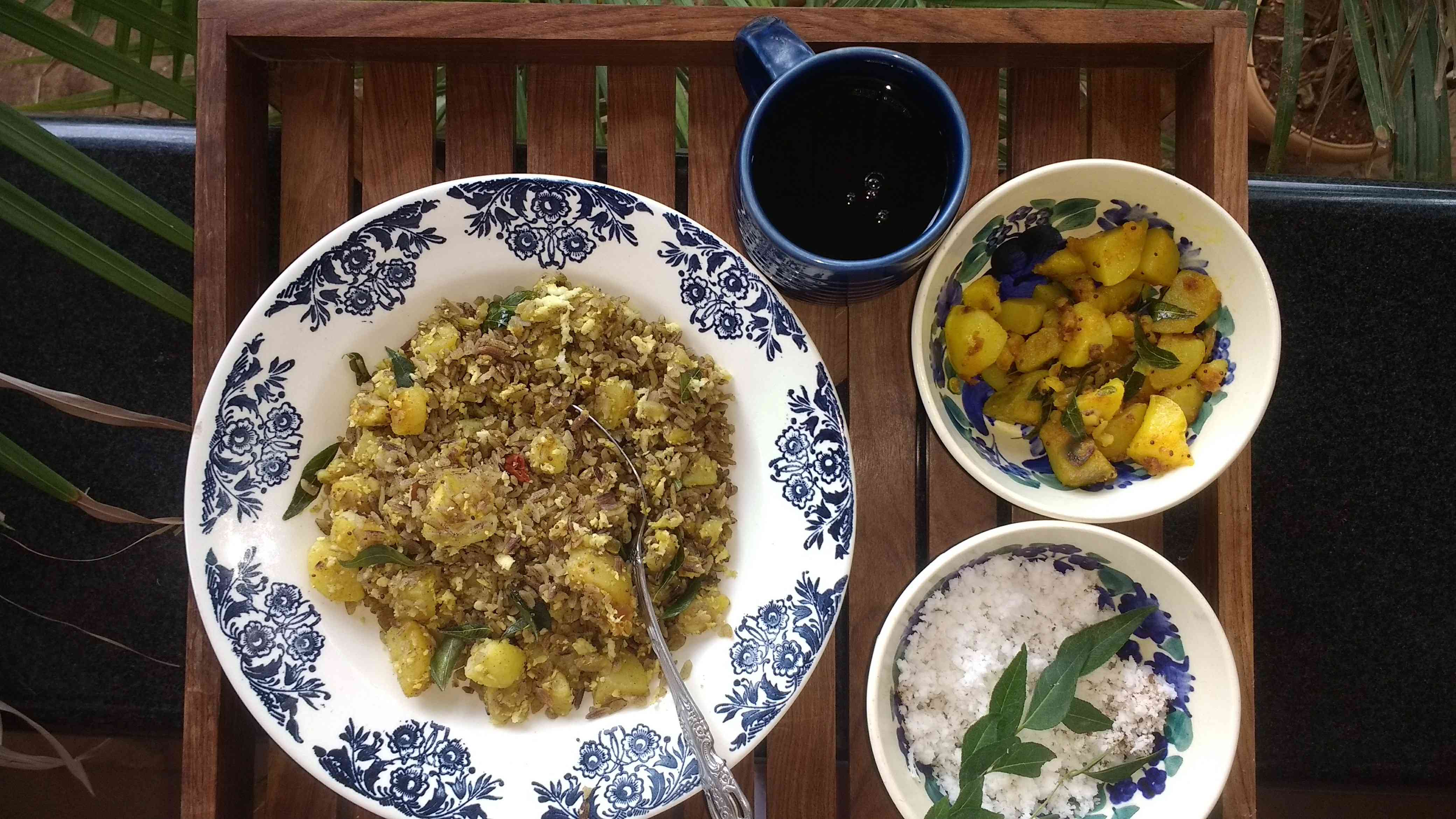

We began the journey with food; organic farmers' markets had begun emerging in many US cities and we found a vibrant weekly market, three miles from where we lived. To get whatever was unavailable there, we would go to the organic superstore in town. They would allow us to take our own containers and pour out grains from bins. The vegetables were not cling-film wrapped individually, as in normal stores. We ended up with good organic food and very low plastic use in the process of buying food. We believe eating organic is one of the best things we can do for ourselves and nature. It reduces the toxin load in the environment and our bodies, promotes the use of less water, and provides a fair livelihood to farmers, the largest segment of Indian society. With that, lovely cloth and jute bags entered our lives. I am so enamoured with the beautiful cloth bags that I end up buying many more than we require. That’s where I fail the first and second tenets of refusing and reducing.

Then we realised that our waste has to be segregated to minimise our contribution to landfills. Whereas the city we lived in the US did not have segregated waste collection, there was a central collection area where we could deposit paper, bottles, and plastic cans separately. We began to do it while advocating our apartment complex to start waste segregation. It was our stay in the Netherlands, a few years later, that taught us how well a people and their government can deal with waste. Sustainable waste management was not the individual’s responsibility or his/her choice in the Netherlands. The law ensured that everybody followed it. There was a waste pick-up calendar, a waste collection tax, and days marked for the collection of each kind of waste—kitchen waste, plastic, and paper. Bottles were disposed of in separate bins for coloured and plain bottles. All old and damaged electronic items which could be handed back to electronic goods shops, were picked up and recycled appropriately. Batteries were disposed of separately. There were large boxes in different parts of the city where old clothes could be donated. Only around 5% of the waste generated went into landfills. The stint in the Netherlands was truly an education in waste management. We personally continue the practice of segregating but struggle to find optimal recycling options. It has to be reiterated that waste has to be segregated at source and not mixed up and sent to the waste facility.

While looking around to buy or build a house, we had the notion that it should be fairly sustainable but didn’t have a clear idea of what it entailed. We are also learning this process as we go along. Finally, as luck would have it, one of my senior colleagues, a reputed environmentalist, contacted us saying that he wanted to sell his house but to a family that was environmentally conscious. We saw the house and he graciously decided to sell it to us. Constructed with baked bricks, unpainted, using almost no wood, the house has a small open courtyard in the centre throwing natural light inside. It also has a ceiling made with a thin layer of concrete laid over baked roof tiles. It is a living, breathing house and is, in some ways, easier to maintain but in some ways harder as the uneven, unpainted surface of the wall attracts spider webs easily. We find more creepies and crawlies around (possibly they find this a comfortable abode) and the brick tiled floors need to be mopped regularly to maintain their sheen. But the house is cooler than most other houses, the brick tiled floor is cool in summer and warm in winter, and when the house gets dirty, all that the walls need is a thorough hosing down. The small garden around the house collects the meagre rainwater. The grey water, which we keep non-toxic by using natural cleaners as well as laundry and dishwashing powders, also goes into the ground. The next step is to build a large sump to collect the rainwater for drinking purposes. This is a constantly evolving project.

We found that sustainability is not one big element but a series of small decisions and choices we make every day or week in our lives, week after week. There are instances where we succeed; in some, we fail; some, we don’t feel convinced about, not because it is not sustainable, but because it is too hard for us to practice. So, for every one of us, it is a journey we have to undertake; the extent of sustainability we practice would vary. However, each of us has a responsibility to try to decrease our impact on the planet and keep our decisions socially and economically fair.

Even though we began our journey of environmental sustainability only in our 30s, our journey with social sustainability began much earlier. I had given up wearing gold in my late teens as I found it obscene that in my home state of Kerala, a marriage involved buying and wearing hundreds of sovereigns of gold, leaving many parents in debt. The mindless accumulation of this metal, which is mined with such environmental and social consequences, has not reduced, even today. My husband was Gandhian from his teens, and simplicity comes effortlessly to him.

We also believe in non-ostentatious celebrations and have always believed that the smaller the celebration, the more elegant it is. So we just moved into our home without much ado; we got our mason to boil the milk in our farmhouse (a hindu house-warming tradition). 25 years ago, we got married with seven people in attendance and recently celebrated our son’s wedding with two receptions attended totally by less than 60 invitees across two towns. Other than immediate family, nobody travelled across cities.

I was always fascinated with cotton fabric and have mostly worn cotton clothes for decades. As I became aware of the travails of the weavers, I moved to wearing mostly hand-woven fabric and buying most of our clothes from weavers' groups and other ventures that ensure a good percentage of the final price to the weaver. Since some years, we have also made it a point to check if these clothes are dyed using non-chemical dyes, not that we have completely moved to vegetable-dyed clothes. We, in India, have such beautiful weaves, natural colours, block prints, that we are spoilt for choice, and we could go through a whole lifetime without using synthetic, non-biodegradable fabric and chemical dyes. This, we hope, will add our bit to supporting weavers and preventing the contamination of water with toxic dyes, and I am sure that not using these toxic colours would be good for our skin as well. This has become an issue close to home, as Coimbatore, where we now live, is an hour from Tirupur, the textile manufacturing and dyeing hub of South India. Every water body in the city is polluted and the water underground is also contaminated with the chemicals used for dyeing. After so carelessly polluting the water, people are now struggling to clean it.

When it comes to sustainability, I think a combination of the public and private is required. Our personal habits have to be combined with effective machinery that encourages sustainable consumption, development of more public facilities, and utilities that aid sustainable living. At the systemic level, the changes in society can be brought about by supportive policies for promoting organic food, waste management, eco-friendly constructions, water conservation and harvesting, air pollution control, weaving, and non-toxic dyeing.

At the personal level, we find sustainability is a mixed bag, just like our house; in parts beautiful, in parts essential, and in parts hard to manage. What we have achieved is baby steps, but the major achievement is the feeling that this is how we want to live. Real sustainability will be achieved only if changes in lifestyle are made without a feeling of deprivation or resentment about having to give up something. Being sustainable is also about living joyfully and mindfully. It doesn’t preclude appreciating beauty and art, enjoying pleasures like a walk, growing a garden, enjoying a book, or volunteering. It is about being and doing rather than owning.

Sreedevi Lakshmi Kutty is the co-founder of Bio Basics, a social venture retailing organic food, and a consultant to the Save Our Rice Campaign

To read more such articles on personal growth, inspirations and positivity, subscribe to our digital magazine at subscribe here

Life Positive follows a stringent review publishing mechanism. Every review received undergoes -

- 1. A mobile number and email ID verification check

- 2. Analysis by our seeker happiness team to double check for authenticity

- 3. Cross-checking, if required, by speaking to the seeker posting the review

Only after we're satisfied about the authenticity of a review is it allowed to go live on our website

Our award winning customer care team is available from 9 a.m to 9 p.m everyday

The Life Positive seal of trust implies:-

-

Standards guarantee:

All our healers and therapists undergo training and/or certification from authorized bodies before becoming professionals. They have a minimum professional experience of one year

-

Genuineness guarantee:

All our healers and therapists are genuinely passionate about doing service. They do their very best to help seekers (patients) live better lives.

-

Payment security:

All payments made to our healers are secure up to the point wherein if any session is paid for, it will be honoured dutifully and delivered promptly

-

Anonymity guarantee:

Every seekers (patients) details will always remain 100% confidential and will never be disclosed