- Home

- Archive -Feb 2002

- The gentle conq. . .

The gentle conquerors

- In :

- Personal Growth

February 2002

By Swati Chopra

For eons, followers of Jinas, the spiritual victors, have walked the Indian soil as living examples of the Jain dharma of ahimsa (nonviolence), satya (truth) and an eco-friendly way of life. In the 2600th birth anniversary year of the last Jain Tirthankar, Bhagwan Mahavir, we look at the relevance today of Jainism’s unique elements like conservation of nature and relativism of truth

|

It’s a cold morning in early January. The sun, enveloped in thick fog, provides little warmth. Wrapping my woolen shawl around my head, I walk briskly to an assignation with a Digambar(sky-clad, as naked and unadorned as the sky) Jain muni (monk).

I catch sight of him from where I take off my leather shoes and empty my leather wallet. He is sitting cross-legged a few feet away, his morpicchi (peacock feather whiskbroom) next to him. He is sky-clad, a complete aparigrahi (one who has no possessions). For more than five decades, he walked the land, in good weather and bad, through forests and mountains, preaching and practicing the creed of the Jinas, the gentle spiritual conquerors. Till the elements no longer bothered him, nor did afflictive emotions. And his body took on the color of the earth he treads.

Greeting me with a toothless smile that transforms his face into the kindest I have ever seen, Muni Vidyanand says: ‘What is Jainism? It is a dharma rooted in nature, as dynamic as it. It is a recognition of the ever-changing nature of reality and a search for that which is constant.’

A quest for what is strong and beautiful and true. A quest as old as humankind. A quest that is at the heart of the Jain dharma of nonviolence and compassion.

AN ANCIENT CREED

Contrary to popular perception among non-Jains, Vardhaman Mahavir, the prince-turned-ascetic who lived 2,600 years ago and was a contemporary of Gautam Buddha, was not the ‘founder’ of Jainism. In fact, there is no concept of a ‘founder’ here. The Jains believe their faith to be an imperishable self-perpetuating one, woven into the ever-moving wheel of time and spooling at its every turn.

During every upward and downward motion of this wheel of time, called utsarpini and avasarpini respectively, 24 Tirthankars (pathfinders) are thought to appear to propagate and revive for their age the eternal truth contained in the dharma. Every Tirthankar is a Jina, he who has attained kevalajnana (infinite knowledge) by conquering his passions, and in his compassion for all beings, builds bridges (tirthas) to enable them across earthly sufferings. The present cycle, thought to be a downward swing, has had its share of 24 Tirthankars, the first of which was Rishabhdev and the last, Vardhaman Mahavir.

Historians have even found evidence of the existence of a Jain-like religion in the Indus Valley Civilization that flourished almost 5,000 years ago. Says Osho, who was born a Jain, in I Am That: ‘In Harappa and Mohenjodaro statues have been found which can only be related to the religion of the Jains—naked statues, sitting in a lotus posture or standing like Mahavir, meditating. Only Jains are known to meditate standing: no other religion has prescribed standing meditation. And they are all naked—only the Jain religion has believed in naked masters. Jain religion seems to be far older than Hindu religion; it must have come from Harappa and Mohenjodaro. They must have been Jain cultures; remnants of it remained and they infiltrated the Aryan mind.’

KAIVALYA, THE ULTIMATE AIM

It is, I think, significant that at the core of this most ancient of world religions is a direct, and permanent, perception of reality, called kaivalya. This supreme state of being is the moksha of the Vedantist, the nirvana of the Buddhist, the satori of the Zen practitioner, the Holy Grail of all spiritual seeking.

According to Jain belief, the individual soul progresses through lifetimes, sloughing off some karmic debts, and incurring others. This cycle goes on repeating until a crucial (human) lifetime is reached where strict penance is required to get rid of the remaining good and bad karma and, more importantly, to conquer once and for all bondage to one’s desires and consequently, to samsara (earthly desires). Kaivalya is the great state of oneness where the soul experiences everything as it is, without the filters and veils of samsara, beyond the strain of constant being and becoming.

|

Of Bhagwan Mahavir’s kaivalya, the revered Jain text, Uttarpurana, says: ‘After fasting for two and a half days, taking not even water, engaged in deep meditation, he (the Venerable One) reached the highest jnana (knowledge) and darsana (intuition), called kevala, which is infinite, supreme, unobstructed, unimpeded, complete and full.’

Then again, in the Kalpa-Sutra: ‘When the Venerable Ascetic Mahavira had become a Jina and an arhat (worthy of worship), he was a kevalin, Omniscient, comprehending all objects. He saw and knew whence they had come, where they would go, and whether they would be reborn as men, animals, gods, or hell-beings. He knew the ideas and thoughts, the food, doings, desires and deeds of all the living beings in the world.’

It is towards this ultimate omniscience experience th at the entire gamut of Jain views, thought processes and conduct is geared and its asceticism, morality and lifestyle focused.

JAIN PARTICLE PHYSICS

Although the concept of karma is present in varying degrees of importance in Hindu and Buddhist streams of thought, Jainism has its own interpretation of it that to me, as somebody not born a Jain, has a ring of familiarity, but then again, not quite. There is, of course, the familiar strain of each act attaining its logical fruition and keeping the soul involved in cyclical births and deaths. Cessation of all karma then is the desired aim.

What Jain philosophy also offers is a detailed understanding and description of the mechanics of the entire process, that in some ways, almost seems borrowed from quantum and particle physics! According to it, the soul-defiling karma actually exists as minute particulate matter in the universe and interacts with the pure, omniscient soul.

Now if the soul harbors any passions or desires, the karmic matter settles upon it and bonds with it, thereby obscuring its pure nature. This soul-karma bondage remains until the fruition of the relevant desire, when the karmic bond falls away like ripened fruit from a tree. But there’s a catch. In bringing that particular karma to fruition, many others have been created. And so the process continues.

In The Scientific Foundations of Jainism, Yorkshire-based scientist, Prof K.V. Mardia divides the entire process in four axioms:

1. The soul exists in contamination with karmic matter and it longs to be purified.

2. Living beings differ due to the varying density of karmic matter.

3. The karmic bondage leads the soul through states of existences (cycles).

4. a) Karmic fusion is due to perverted views, non-restraint, carelessness, passions and activities.

b) Violence to oneself and others results in the formation of the heaviest new karmic matter, whereas helping others towards moksha with positive nonviolence results into the lightest new karmic matter.

c) Austerity forms the karmic shield against new ‘karmons’ as well as setting the decaying process in the old karmic matter.

Prof Mardia goes on to discuss the soul-karmic matter (which he calls ‘karmons’) bonding in terms of interactions between quarks, leptons and gauge bosons, three elementary particles being researched in modern particle physics.

MY TRUTH, YOUR TRUTH

That is not all, however, that is of interest in Jainism to contemporary minds. There is something uplifting and liberating, and thus germane, about an ancient faith that looks at the world with a complete openness towards its many different ‘truths’. At a time in history when every religion, ideology and economic system claims to possess the best, most successful, superior-most truth, the gentle Jina whispers reassuringly: ‘My truth is fine from my standpoint, and so is yours!’

In the past few decades, there have been, in many small ways and in different parts of the world, efforts to move towards societies that embody not only ‘unity in diversity’, but more importantly, ‘diversity in unity’. As the world begins talking about integrating the voice of the ‘other’, the subaltern, the dispossessed, the marginalized, into a plural, multicultural, multiethnic society, I think it’s time the twin Jain ideals of the manyness and relativity of truth (anekantavad-syadvad) are reexamined.

In The Jain Declaration on Nature, presented to HRH Prince Philip of England, eminent scholar and Chancellor of the Jain Vishwa Bharati (Deemed University), Dr L.M. Singhvi explains: ‘Anekantavad, or the doctrine of manifold aspects, describes the world as a multifaceted, ever-changing reality with an infinity of viewpoints depending on the time, place, nature and state of the one who is the viewer and that which is viewed.’

About syadvad, he says: ‘Anekantavad leads to syadvad or relativity, which states that truth is relative to different viewpoints. Absolute truth cannot be grasped from any particular viewpoint alone because it is the sum total of all the different viewpoints that make up the universe.

‘Because it is rooted in the doctrines of anekantavad and syadvad, Jainism does not look upon the universe from an anthropocentric, ethnocentric or egocentric viewpoint. It takes into account the viewpoints of other species, other communities and nations and other human beings.’ Ideal for successfully managing conflicts, nations, relationships, lives!

|

Ganini Pramukh Shri Gyanmati Mataji, a Digambar Jain sadhvi (nun) from Jambudweep, Hastinapur, India, explained these abstract concepts in more homely terms to me: ‘If a man is a father, he is so in relation to his son. If someone is an uncle, he is so in relation to his nephew or niece. That is one of the things he is, he is not simply an uncle. That is a relative truth. And syad means ‘from one point of view’ and vad means ‘to say’. So we can say, from one point of view, this person is a father, from another he is a son, and maybe from others, he is so many different things.’

Intolerance creeps into attitudes with an unwillingness to accept difference. Of beliefs, skin color, race, gender, caste, clothes. An acceptance with open arms of otherness and difference lies at the heart of anekantavad, and it is here that ahimsa, abstinence from violence, really begins.

Says DR V.P. Jain, director of the Bhogilal Leherchand Institute of Indology: ‘Anekantavad says in effect, ‘you are right, but I am also right’. Each one of us has a personality that has been created by our circumstances. So we cannot expect everybody to have the same view as us! And so, in a conflict, the anekanta viewpoint helps move towards ahimsa or nonviolence. In the inclusiveness of anekanta lie the seeds of true ahimsa. This translates into a deep reverence for all life, without which there is no anekanta.’

DHARMA OF AHIMSA

‘All of Jain philosophy and ethics can be explained in one word—ahimsa,’ points out an ascetic from Gyanmati Mataji’s entourage. Indeed, the Jain dharma has perfected nonviolence not only in action, but in thoughts and ideas as well. The Jain way of life is a perfect exposition of the ancient Sanskrit saying: Ahimsa paramo dharmaha, ahimsa is the supreme religion.

According to Jain philosophy, the densest karmic defilement of the soul takes place when one causes hurt to any other creature. Hence the high place accorded to nonviolent conduct. This is also the motivation behind many Jain practices that seem strange and even somewhat eccentric to non-Jains. These include strict vegetarianism to the extent of even avoiding vegetables that grow underground, abstinence from food and water after sundown, sweeping the ground by ascetics as they walk, use of a strip of cloth over the mouth by Terapanth Shwetambar ascetics, the pulling out of their hair by sadhus(monks) and sadhvis (nuns), and so on. All these practices have to do with avoiding even unintentional harm to any other creature.

Says Jitubhai Shah, director of the L.D. Institute of Indology in Ahmedabad, India, and a practicing Jain: ‘The Jain lifestyle is a perfect enunciation of ahimsa. Even the rigid principles make a lot of sense, if you really examine them. For instance, the reason Jains don’t normally eat or drink anything after sundown is because it is believed that doing so would cause the death of minute microorganisms that emerge in the dark. The entire lifestyle is geared towards causing least harm to other creatures and the environment, although for life activities, some harm is unavoidable. One can begin doing this by opting for products and practices in which minimum violence is involved.’

COMPASSION FOR ALL BEINGS

A natural corollary to nonviolence is jiva daya or compassion towards all, the importance of which cannot be emphasized enough in today’s ‘eye-for-an-eye’ world. As DR Singhvi says in The Jain Declaration on Nature: ‘Ancient Jain texts explain that it is the intention to harm, the absence of compassion, that makes an action violent. Without violent thought there could be no violent action. When violence enters our thoughts, we remember Mahavir’s words—you are that which you intend to hit, injure, insult, torment, persecute, torture, enslave or kill.’

Agrees Jitubhai Shah: ‘Ahimsa or nonviolence is not only non-killing, it also means that one’s attitude must be of maitri(amity) and peace. The real meaning of ahimsa is maitri. There are thought to be countless jivas, life or life forms, that populate the earth, air, water and are present all around us. How are we to behave towards these? With maitri.’

A beautiful example of this jiva daya is epitomized in the Charity Birds Hospital in the Digambar Lal Mandir complex in Old Delhi, India. The only one of its kind in the world, the hospital was founded in 1929 by Laccho Mal Jain. He would sit in the temple every evening and often see birds fly into the temple’s ceiling and get hurt. Looking to relieve their suffering, he devoted one room in his house for treating sick birds. Today, the hospital is housed in a two-storied building and even has an OPD and has a separate floor for convalescing birds.

People from far and near often write in for advice on bird diseases. A young boy, Irfan, who brought his sick pigeon to the OPD while I was there said: ‘Whenever any of my birds is sick, I rush it to this hospital. Afterwards, I let the hospital staff release them.’ A Jain restaurant owner in nearby Chandani Chowk, Delhi says: ‘Sometimes when birds fly into the fans in my restaurant and are injured, we take them to the bird hospital. As a Jain, this is my small way of following jiva daya.’

Another aspect of jiva daya are the large-scale charitable activities undertaken by Jains. Rupali Mehta, a trustee of the Mumbai-based Diwaliben Mohanlal Mehta Charitable Trust, says: ‘I was inspired by my grandfather-in-law, Mafatlal Mehta, founder of the Trust and a staunch Jain. I believe that the heart of Jainism is its focus on serving and helping humanity and, indeed, all life. There are nine punyas (good karma) in Jainism some of which are anna daan (donation of food), jal daan (donation of water), vastra daan (donation of clothes) and so on. If you go to any Jain temple you will find many donation boxes, including one marked pashu daan, for the welfare of animals.’ The trust’s activities include 30 boarding schools for girls in Maharashtra and Gujarat, India, a residential school for blind girls, and a home for destitute women. The trust also sponsors patients for treatment.

MAHATMA GANDHI’S JAIN GURU

It is little known that the apostle of nonviolence, Mahatma Gandhi, had a Jain ‘spiritual mentor’, a young diamond merchant, Shrimad Rajchandra. Once, in despair, Gandhi wrote to Shrimad Rajchandra that he wanted to change his religion. Rajchandra, a householder-ascetic, asked him to look within himself first. This changed Gandhi’s life. Thereafter, he would often say that he had learned most of his lessons of self-improvement, truth and nonviolence from Rajchandra’s Jain views. In fact, Rajchandra, who died young at the age of 33, is one of the three whom Gandhi considered as having been instrumental in molding his ideas, the other two being the writings of Leo Tolstoy and Ruskin’s poem ‘Unto this last’.

THE GREEN RELIGION

Ahimsa and jiva daya have made Jains great environmental conservationists. Eco-friendliness is interwoven into their day-to-day living and is based on a feeling of being trustees of the earth. ‘We are like the adivasis or tribals,’ says Muni Vidyanand, ‘We exist in harmony with the earth. The earth takes care of us, and so we take care of her. Man has polluted the earth because he thinks of her as a possession.’ He picks up a speck of dust. ‘Tell me, who owns this?’

An attitude of reverence towards the earth, air, water, stems from the Jain belief that everywhere exist beings in different forms and in various stages of spiritual evolution. So if I cut a tree, I have killed a jiva (life) and therefore caused violence.

|

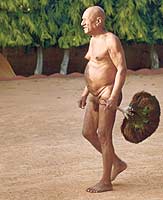

Ordained Jain ascetics of all sects, till today, travel on foot. The Shwetambars wear white cotton cloth, and the Digambar monks remain naked. The former eat twice a day, the latter once and that too using their palms as plates. As Jitubhai Shah points out: ‘The lifestyle of Jain monks is the way of least violence. They don’t use any vehicles and eat only to sustain themselves. Their eating is called gochari, the way the cow eats, a little from here and a little from there, so that no one is burdened.’

These activities, which make the life of Jain monks and even the laity, seem harsh are actually calculated to increase one’s awareness of one’s immediate environment. The only other possession that Digambar monks carry is a broom of peacock feathers to sweep away insects. And the third article of clothing allowed to Terapanth Shwetambara ascetics is the ‘muhpatti‘, a strip of cloth to mask their mouth so that the stream of moist air from it does not cause the minute single-sense organisms present everywhere to perish.

Lives lived simply, in awareness, with no strain on the land’s resources and in recognition of the ideal: Parasparopagraho jivanam, which means that all life is bound together by mutual support and interdependence.

A JAIN MONK-ACTIVIST

In the January/February 2002 issue of the UK-based eco-spiritual magazine, Resurgence, editor Satish Kumar talks about meeting a Jain monk, Hitaruchi, in Palitana, a Jain pilgrimage place in Gujarat, India. Hitaruchi is a diamond merchant turned monk who has consciously switched to organic food, handmade utensils and renewable fuels. Satish quotes this ‘prophet of Jain ecology': ‘Nonviolence is not just a matter or personal behavior. Nonviolence includes social, political, economic and ecological dimensions. If there is social injustice, political oppression, wasteful industrial production and destruction of natural resources, then it is impossible to practice nonviolence.’ Muni Hitaruchi, says Satish, is walking from village to village ‘asking people to seek contentment in quality of life rather than in the quantity of material possessions.’

I OWN NOTHING

Hitaruchi’s message, as indeed that of Jain dharma, sorely begs to be heard above the din of ‘yeh dil maange more‘ (the heart desires more, a very catchy phrase in India these days). Indeed, as the winds of materialism and consumerism blow forcefully across the country, we need to plant our feet more firmly in our soil and turn within. And perhaps remember the Jain ideal of aparigraha when toying with the temptation to buy an umpteenth pair of Levi’s jeans.

A-parigraha literally means nonpossession, although it can also mean nonattachment to possessions. Among Jain ascetics, this is evidenced in the literal giving up of all possessions. At various other levels, it might also be interpreted as ‘letting go’ of attachments to objects, and even people and relationships. The complete aparigraha of the Jinas is often depicted in Jaina sculpture by showing the Jina in the kayotsarga (abandonment of the body) position—standing up straight, hands hanging by the side, noble and beautiful.

This abandonment of the body has acquired the form of the Jain practice of sallekhana, or voluntary death.

DEATH BY CHOICE

I remember the first time I heard of sallekhana. It was from Satish Kumar, who had been a Jain monk for many years in his youth, before becoming a Gandhian. Satish’s mother, to whom he was very close, had performed sallekhana after living to a ripe old age. ‘After receiving permission from her guru, she went to all her relatives and asked their forgiveness. There was an air of festivity in our home as she began fasting. First she gave up food, and then water. After a few days, she died peacefully.’ I looked at Satish’s face for any hint of pain. There was none.

Sallekhana, the ultimate aparigraha, must not be mistaken for suicide. Explains Muni Vidyanand: ‘Try and live life fully till the last moment. But when you feel that death is near, you must leave all else and turn inwards. Sallekhana is the Jain way of making death a time for contemplation and celebration, and not mourning. Every creature instinctively knows the time of its death. A tiger, when it knows that it is going to die, lies down quietly and refuses to eat. Sallekhana is a brave way to die, it is an embracing of the inevitable, instead of trying to run away from it.’

GENDER (IN)EQUALITY

Interestingly, it is the definition of aparigraha, among certain other beliefs, that caused the Jain society to split into Shwetambars (white-clothed) and Digambars (sky-clad). Complete aparigraha is an essential prerequisite for kaivalya in Jain dharma. The Digambars interpret this as meaning the casting away of all possessions, including clothes, whereas for Shwetambars it is more a state of mind.

This has, in turn, given rise to other debates, like that over enlightenment for women. Since women could not be allowed to go naked, not even for so august a cause as enlightenment, Digambars deny that women can attain kaivalya. The Shwetambars, of course, do not face this dilemma and even take the 19th Tirthankara, Mallinath, to be a woman.

To get a woman Digambar’s view, I asked Gyanmati Mataji about this. ‘A muni (monk) owns nothing, not even clothes, and it is only in that extreme form of aparigraha that kaivalya is possible. A Jain sadhvi (nun) cannot do complete aparigraha, she has to have at least two saris. As a woman, I will have to escape this form first and move towards the deva (God) form. And then from there to the human male form in which again I will have to do the requisite penance for kaivalya. This is what the Digambars believe in. I agree with this totally.’

As a woman interested in enlightenment issues, I probably looked horrified. Aryika Chandanaji, Gyanmati Mataji’s prime disciple, noticed the look on my face and laughed: We need not worry too much about that, because in this era, the men are also not getting anywhere

To read more such articles on personal growth, inspirations and positivity, subscribe to our digital magazine at subscribe here

Life Positive follows a stringent review publishing mechanism. Every review received undergoes -

- 1. A mobile number and email ID verification check

- 2. Analysis by our seeker happiness team to double check for authenticity

- 3. Cross-checking, if required, by speaking to the seeker posting the review

Only after we're satisfied about the authenticity of a review is it allowed to go live on our website

Our award winning customer care team is available from 9 a.m to 9 p.m everyday

The Life Positive seal of trust implies:-

-

Standards guarantee:

All our healers and therapists undergo training and/or certification from authorized bodies before becoming professionals. They have a minimum professional experience of one year

-

Genuineness guarantee:

All our healers and therapists are genuinely passionate about doing service. They do their very best to help seekers (patients) live better lives.

-

Payment security:

All payments made to our healers are secure up to the point wherein if any session is paid for, it will be honoured dutifully and delivered promptly

-

Anonymity guarantee:

Every seekers (patients) details will always remain 100% confidential and will never be disclosed