- Home

- Archive -Mar 1997

- The world in a . . .

The world in a grain of sand

- In :

- Personal Growth

March 1997

By Amit Jayaram

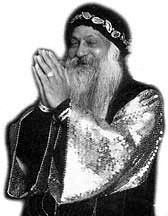

The story of Osho—master, mystic, madman

Trying to define Osho is like trying to imprison a rainbow or catch a cloud that’s floating through your room.

|

Like sand, he slips through your fingers: like a sparkling drops of dew, his magic vanishes with the rising sun of definition.

Samuel Johnson, in his Preface to Shakespeare, says that Shakespeare is not a pretty garden, but a great forest, a forest that is wild and wonderful.

So is Osho. And it is his wildness that is his greatest flavor. A trip with Osho is no picnic for socialites or fingernail-clicking namby-pambies. Osho’s sweep is as vast, as majestic, as diverse, as unpredictable as life itself.

There is majesty here, but danger too. Far past the comfortable backwaters of respectability, morality, ethics and so-called sanity, we find ourselves on the high seas of life, with no buffers between us and the elemental powers of the universe.

And our captain, far from sheltering and consoling us in this our first assay into the world of the uncharted, pushes us into the danger. He removes our props, throws away our crutches, destroys our conditioning, tramples on our most cherished beliefs and abandons us, naked and unprotected, to the gigantic waters of the cosmos.

Most of us are too scared to even allow him to take us thus far, and run away, often without even trying to find out what he is really saying. But even amongst those of us who walk some steps with him and encounter the utter nakedness of floating on the high seas of life, almost none of us can deal with the feeling of being unprotected, unguarded, unprepared. We are terrified and rush back, often swearing never to go again.

But there is something haunting about the experience. Almost against our will, we wander into this boundless ocean again. An ocean called meditation, where we turn inward to face ourselves. Despite the confusion. Despite the fear. Despite the darkness, the absence of the comfortable, the familiar.

Slowly, hesitantly we enter this space. Where, with William Blake, we see ‘the worlds in a grain of sand, heaven in a wildflower, hold infinity in the eternity in an hour’. This is the oceanic world. The world that is Osho…

BUDDHAM SHARANAM GACCHAMI

‘Somebody anonymous, somebody who is more a nobody than a somebody; a man who has died long ago as a separate entity…’

Where does one begin? At the beginning? One wonders. Because this story is as much about time and space as it is about here and now, about eternity. Because this is the story of one who was never born, never died. One who visited plant Earth briefly, and left his gentle imprints on the measureless sands of time.

As a child growing up in the grace and openness of total freedom a gift from his wonderful grandparents. As a young adult, exposing the stupidity of a bankrupt educational system with the scalpel of an incisive mind and penetrating insight. As Acharya Rajneesh, roaming the vastness of India to encounter people, to enchant them with his incomparable oratory, to help them transform themselves with the Dynamic Meditation he devised for our troubled age. As BhagwanShree Rajneesh, immobile in Pune, western India, the wanderer in him dissolving into the sage, creating a vibrant ‘Buddha field’, a crucible of the spirit where countless seekers absorbed the energy and used the techniques made available to trigger the process of self-discovery.

As Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh in the Oregon days, when he and his sannyasins transformed the face of a timeless desert into a green and beautiful land before (according to Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh Poisoned by Ronald Reagan’s America by Sue Appleton) a bigoted government threatened by his extraordinary insight and unparalleled courage, used every foul means at its disposal to poison him with long-acting thallium, depart him and prevent some dozen world governments from entertaining him, in the ugliest way possible. As Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh of the World Tour days, when nation after nation passed beneath him like the fleecy clouds beneath the wings of a plane, and his fiery discourses in Greece, in Uruguay startled a shell-shocked world into awareness.

As Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, in the days when he returned to his commune in Pune, his discourses were initially as fiery as those he delivered during the Oregon and World Tour days. But they soon mellowed into the most deeply meditative ones he had ever given—they veered towards Zen and, for the first time, began to include group meditation. A couple of years after he came back home, the Acharya who was Bhagwan became Osho, the oceanic one.

And that’s all there was, because soon the thulium administered to him by the US authorities when he had been arrested without a warrant and spirited away to parts unknown (documented by Appleton), began to take effect. His failing health started affecting his work. His regular discourses were interrupted repeatedly. Eventually, he surrendered to the effects of the poisoning; a life rudely cut short, when the world could have benefited from fresh insights and his unique wisdom for many more decades.

These details are insignificant trivia. Like looking at the grooves on a gramophone record reveals no mysteries about the music they contain, these biographical benchmarks say little about the spirit, the genius and the effortless ebullience that is Osho. The tense I use is important. His leaving the body has had little effect on his living presence. Whether in the OshoCommune International in Pune, at other communes and meditation centers around the world or wherever his sannyasinsand lovers gather in his name, hear him, read him, or talk about him, Osho is tangibly present.

What he called the Buddhafield in Pune is the very matrix of the energy field he created around him and has a very powerful and immediately tangible presence even today. His is a presence that pervades the world.

Every day, new people take their first hesitant steps towards him and slowly slip into the silence of his presence, the fathomless depths of his insight, the healing aura that emanates around him.

Like most enlightened masters, Osho was continuously misunderstood by small minds soaked in prejudice, and fell prey to the gratuitous violence of man—like Jesus and Socrates before him. His truth was too incandescent, his candor too blinding for men who had lived in darkness all their lives.

He held the mirror up to us, to reflect our follies, our prejudices, and our superstitions; our implacable and adamantine conditioning that holds us prisoner all our lives. But we were too fainthearted to look. And a vast majority of those who looked, looked briefly, were terrified of their reflection and railed against the mirror.

It is far easier to break the mirror and not have to see our tortured reflection. To look, accept, admit and begin the arduous journey of transforming oneself is difficult, well-nigh impossible. When the mirror that was Jesus reflected us, we crucified him. When the mirror that was Socrates reflected us, we poisoned him. A similar fate was reserved for Osho. We human beings certainly have a strange way of saying ‘thank you’ to the enlightened beings that make their effulgence available to us.

What did Osho do? He told us to give up our phony adherence to an ossified past that haunted us, and live in the moment, use the alchemy of meditation to transform ourselves—to become Christs, not Christians; Krishnas, not Hindus; Buddhas, not Buddhist. His crime was that he spoke the truth.

He dared to tell us that sex was the first rung of the ladder to super consciousness; that unless we accept the rung and use it as a stepping stone, we would be stuck forever—the very energy that is sex is transmuted into super consciousness. We continued to sweep sex under the carpet or indulge in it, and called him a Sex Guru.

He dared to expose the deep nexus between priests and politicians that has kept humanity enslaved from beginningless time. He showed us how the priest uses the carrot of heaven and the stick of hell in the matrix of a psychologically nonexistent past and future, how he creates guilt and fear and then provides panaceas for it. How the politician divides us into fragments and then speaks of uniting us; creates hatred and ill will, then talks about universal brotherhood; creates and espouses the divisiveness of nation states and then gives it a sanctity that can demand sacrifice. We continued to run like frightened rabbits into the warrens of a bankrupt society and organized religion, and called Osho dangerous, the antichrist, the unbeliever.

Prophets are often ahead of their time, but Osho was centuries ahead of his. When his majestic vision showed us a brave new world, we hung on to the apron strings of society and church, tradition and conditioning, and huddled deeper in the cavern of our own little selves.

In his masterpiece, A Marriage of Heaven and Hell, William Blake says that if the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is, infinite… But man has closed himself up till he sees all things through the narrow chinks of his cavern. But it is never too late.

The italics in ‘as it is’ are mine. That’s what Osho said again and again all his life, but our conditioning didn’t let us hear. He said we were all Buddhas, gods in exile; that God was not separate from existence, but immanent in existence-only God is an all is God.

Osho may not be in the body, but his spirit is ever present, ever available, his Buddha field of transformation a tangible reality. Never born, never died—just visited Planet Earth. He can still catalyze an unprecedented change in your life today.

All you have to do is visit his Buddhafield in Pune, read a book, listen to a tape. And watch the magic unfold within you.

DHAMMAM SHARANAM GACCHAMI

‘Life is not a problem to be solved, it is a mystery to be lived…’

Osho’s basic message is no message. His basic teaching is no teaching. He doggedly opposed the creation or following of philosophies and ideologies. Although he spoke on more scriptures than anyone else in the history of human consciousness—and with the greatest authority on subjects and people ranging from subatomic physics to Vincent Van Gogh, Karl Marx and Freud—he warned against following scriptures and underlined the great danger of knowledge; he repeatedly emphasized the importance of one’s own experience and the danger of imitating others, no matter how enlightened.

This applied as much to him as to anyone else. Although he emphasized the need for a guru, he stressed that it was not the truth, but a necessary evil. That, after crossing the river, the raft becomes a hindrance if still carried. That, when more gross and mundane obstacles have been overcome, the guru becomes the obstacle and has to transcend.

He spoke on almost every mystic this world has had the privilege to witness with such insight that they sprang to life; their presence became a living reality while his enlightenment breathed life into them again. And yet he offended more people by criticizing messiahs and prophets than anyone in the history of humanity. He did this with the professed intention of what he used to love calling ‘hammering’—a process of deep reconditioning by challenging and uprooting the deepest and most cherished beliefs of a person. It is only a wholly de-conditioned person, he said, who has the innocence, the fluidity, the effervescence to dissolve into the totality, without leaving a trace.

One of Osho’s most significant contributions to the seeker of this age, and ages to come, is the breathtaking clarity he brought to the critical, perhaps preeminent, importance of the here-now.

Osho was controversial and reviled purely because he lived this insight—he didn’t just talk about it. He repeatedly said that there is only one world, one space, the here and now. That it is journeying from one place to another, not this so-called phenomenal world that is the real sansar. That being here-now, not journeying at all, is the end of the sansar. That ethics and morality and respectability are false coins. That people who give you goals—no matter how laudable—are your enemies, because goals create the future, and trigger the debilitating mechanism of desire. That people who tell you how to become and what to become are the poisoners.

Such a person cannot draw lines between the good and the bad, the sacred and the profane. Osho always said that divinity is not separate from existence it is immanent in existence. As Blake said, all that lives is holy. He also continuously emphasized that the divine is not separable from existence, like a painter from his painting. It is integrally connected with existence, like a dancer with his dance. Which is why he used to say again and again that, if there is such a thing as the divine, it is not a noun but a verb; not a persona but a process; not a creator, but creativity.

A person like him has eyes to see. He can see that there is only one energy. It can be blocked or freed. The energy freed from the repression of sex, or indulgence in it can become the ladder to super consciousness. He can see that energy always flows towards the source of the greatest joy—when the window of meditation opens, the energy that was sex, was attachment, was greed, gets absorbed and subsumed by it. That prejudice, no matter how ancient and hallowed, must be destroyed if one wants the authenticity that is the first prerequisite to the unfolding of our hidden splendor.

Osho also revealed a great secret to us—do not fight with darkness. It is nonexistent and therefore impervious to struggle. He used to say that when we want light in a room, we do not push the darkness out; we merely light a candle. And the darkness of a million years has no resistance; in just a moment a small candle dispels it. Osho likens all our negative qualities to darkness, and calls all ethics and morality an effort to fight with darkness and therefore doomed to fail. The nature of all ignorance and all unconsciousness is the nature of darkness. The only way to dispel it is by bringing light in—the light of love, the light of meditation.

Another very critical contribution from Osho was a strong insistence on change in daily life. He repeatedly said that one should renounce the mind, not the world; that those who renounce the world are nothing but escapists. A monk renounces the world, the crowd for 30 years, but he still remains a Hindu, a Christian, a Buddhist. And to be a Hindu, a Christian, a Buddhist is to be part of a crowd. The individual can be a Christ, but not a Christian.

This is reflected in his notion of sannyas, which he called Neo sannyas. It is revolutionary. There are no vows. No bindings. The only vow an Osho sannyasin takes is a commitment to himself, to meditate. Osho always said that his sannyasin is truly like a lotus flower. She lives in the world, but the world does not live in her, just like the lotus rises above the dirty water of the lake it grows in.

Osho revolutionized meditation as we know it. He contributed scores of new and innovative meditations to the world.

Osho felt that, in the days of old, sitting meditations were beneficial to large numbers of people, because life was less stressful, living simpler. In modern conditions, the mind and body rebel against it. And any force is unnatural and harmful. It leads to what Osho called a state of inner civil war, which dissipates energy and is very destructive.

Osho’s dynamic meditations begin with activity like jumping or dancing. After some time, when the body is naturally tired and the mind calmed by physical activity, the mediator sits, or lies down, to meditate—in consonance with nature, not struggling against it.

Osho brought laughter back to religion. He used to be very fond of saying that guilt is a state of sickness, that seriousness is pathological. Far from the somnolent and lethargic atmosphere one still associates with religion, his commune and his discourses were distinguished with laughter, ebullience and vivacity. Words like joy, celebration, fun and festivity are key words—not in terms of significance, but in their actualization in the here-now he inhabited.

No one used as wide a variety of jokes and anecdotes with consummate skill as Osho, to slip skillfully past conditioning and break down barriers. His discourses, whether on masters and mystics or responses to daily life questions, were filled with vitality and energy—they throbbed with intensity and passion.

Osho’s discourses, meditations, and the energy he shared with his sannyasins and lovers did more than give a delightful freshness, an enticing now-ness to the quest for self-awareness. His words and his life exemplified another unique ability: the ability to simplify, deconstruct and explain some of the most nagging mundane problems that beset humanity. He was also without doubt a psychotherapist par excellence, and took psychotherapy beyond its own frontiers—helping a person adapt to a neurotic society—into the vistas of meditation, freedom from all conditioning, and enlightenment.

To me, Osho represents the omega point of the entire spiritual history of mankind. He is the first enlightened master who had the environment and ability to assimilate the million facets of our spiritual heritage into a laser beam-like precision, without losing the flavors, the richness, and the diversity. In a world that had become a global village, Osho had the ability to soak himself in all the religious, social, cultural and intellectual traditions of mankind. And he had the inner depth, breadth, expanse and insight to transmute them into a vision both uniquely his own and man’s heritage since eternal time.

Some centuries from now, when a more placid humanity views Osho in tranquility, they will see him as he is, always was and will be: a world in a grain of sand. For a grain of sand hides the subatomic dance. And it is a grain of sand that makes our spectacular universe a living reality.

SANGHAM SHARANAM GACCHAMI

‘I want to sabotage that stupid idea of an ashram: that it should be dead, people should be inactive, dull, uncreative, against life, against love…’

One of the most famous tourist hand marks in India is no monument weathered by age, or the ruins of a city made famous by some bloodthirsty army or empire. It is the Osho Commune International in Pune.

Located in Koregaon Park, the Osho Commune attracts thousands of sannyasins and lovers of Osho who make up a sizeable portion of the floating population in the city.

Who are these people? Why are they attracted to Osho? Why are they so controversial? And what exactly happens in the Osho Commune to make people flock there?

One of the most significant aspects of Osho’s vision was his notion of the New Man, who would be integrated and total. Such a man would be beyond belonging to a religion, a nation, and a caste, even the gender that the phrase implies. The New Man would also be free of the schism between the inner and the outer. He would, in Osho’s words, be Zorba the Buddha. Combining the deep meditative vote of the Buddha with the passion and intensity of Zorba the Greek, he would be a true individual, free of social programming—centered and equanimous, yet full of zest and love of life, with great inner and outer richness.

The Osho Commune is a concrete example of this synthesis, this holistic view of life. William Blake says that as the caterpillar lays its eggs on the fairest leaves, so the priest lays his curse on the fairest joys. The commune is a celebration of freedom from the schism between body and spirit, artificially created and exploited by priests and politicians. The New Man says yes to both and no to nothing. Thus, he is wholeness, a totality not torn apart by conflict. And in him, the seed of a new future beings to take birth.

The commune is an exemplification of communism with a spiritual base. It is a gathering of individuals, not a crowd of people. Individuals coming from the space of freedom to experiment with freedom. This creates what Osho called a Buddha field, a place where individual seekers can gather with other individual seekers in the voyage of self-discovery.

In the commune, distinctions are dissolved. Identities and conditioning slip away. Religion and race, nationality and caste, gender and status, color and creed disappear in the oneness of meditation and inner exploration. Everyone functions simply as a human being, growing and evolving into the divinity that is their true nature and birthright.

The commune is a model, a family of the future. A relationship within the existing family structure is not possible because it is a relationship of mutual possessing and being possessed, with love and freedom sacrifice at the altar of dependence and expectation. People become roles and functions, and relating becomes impossibility. This is a new family structure, free of possessiveness and expectation, based on interdependence, on interconnectedness. The growth of the commune is the growth of individuals, and the growth of individuals is the growth of the commune. This is what makes the difference. The commune is an authentic space, not a conditioned reflex.

One of the most significant aspects of this dissolution is the dissolving of gender. For the first time perhaps in the history of humanity, women can down the yoke of subservience and be truly creative. Osho used to often say that, with the suppression of women, 50 per cent of the world’s creativity has not been allowed to blossom. If this hadn’t happened, our world would have been a different place. In the commune, a woman can do anything form welding to Japanese gardening, free of role expectations and gender stereotyping.

Being a part of the commune also involves a change in gestalt. We normally look for what we can get, not what we can give. In the commune, two primary principles operate. Contribution. And meditation. Both help the individual and the commune, but in different ways.

Contribution allows the seeker to give her time, her energy to the needs of the commune—but this benefits her immensely too because it has a strong therapeutic element. In the easy confluence of the sangha, it is easier to empathize, to drop the ego, to surrender totally.

Meditation helps the seeker in her own development. But the atmosphere, the energy of meditation permeates the space and contributes in a large measure to the Buddhafield, which nourishes the entire community.

The commune is a laboratory of the spirit, free of respectability, so -called morality and ethics, of meaningless outdated taboos that still torment an unconscious humanity. In the commune, the seeker has access to a wide variety of meditations as well as an incredible range of group therapies to unburden guilt, dissolve age-old fears, obsessions and prejudices.

No one was a greater lover of all that is aesthetic than Osho and his Commune reflects it, reveals it, and resonates with it. Interwoven with vegetation and peopled with creatures coexisting with seekers in their natural habitat, the commune is an aesthete’s paradise.

The Buddha Hall, which can seat as many as 10,000 people used to play witness to Osho’s discourses. Today, it is the main center of meditation through the day, followed by an evening celebration called the White Robe Brotherhood, in which seekers, Osho lovers and sannyasins dress in white robes and gather to sway to live music, dance and submerge themselves in the here-now, before they see a video recording of an Osho discourse.

Apart from the aesthetic environs, the commune is a nerve center of creative activity. Theater, music, dance, painting are woven into the life of the commune. There is tennis, called zennis, swimming, and the martial arts the commune is buzzing with activity. Everywhere, energies are creating, whether in the silence of meditation or the music of relating and creativity.

The commune is perhaps one of the very few places in the world, which are truly modern. Here, the anachronistic baggage of the past that we tend to carry with us is truly forsaken, as are the taboos and conditioning we have too long taken to be ourselves. It is a center of freedom and love, where the individual vibrates in harmony with other individuals and the Buddhafield they create around each other. In an easy and fluid atmosphere, seekers contribute, meditate and grow, in the grace of individuality—in the beautiful environment of their sangha.

To read more such articles on personal growth, inspirations and positivity, subscribe to our digital magazine at subscribe here

Life Positive follows a stringent review publishing mechanism. Every review received undergoes -

- 1. A mobile number and email ID verification check

- 2. Analysis by our seeker happiness team to double check for authenticity

- 3. Cross-checking, if required, by speaking to the seeker posting the review

Only after we're satisfied about the authenticity of a review is it allowed to go live on our website

Our award winning customer care team is available from 9 a.m to 9 p.m everyday

The Life Positive seal of trust implies:-

-

Standards guarantee:

All our healers and therapists undergo training and/or certification from authorized bodies before becoming professionals. They have a minimum professional experience of one year

-

Genuineness guarantee:

All our healers and therapists are genuinely passionate about doing service. They do their very best to help seekers (patients) live better lives.

-

Payment security:

All payments made to our healers are secure up to the point wherein if any session is paid for, it will be honoured dutifully and delivered promptly

-

Anonymity guarantee:

Every seekers (patients) details will always remain 100% confidential and will never be disclosed