- Home

- Archive -Nov 2010

- Through the min. . .

Through the mind and out

- In :

- Personal Growth

November 2010

By Purnima Yogi

Jnana Yoga, or the path of the intellect, is tailored to the modern mind. Here, the seeker takes nothing on trust. Instead, he uses the mind like a laser to penetrate the illusions of maya until only the truth remains. That God alone is

|

At 16, I thought my life would be like anyone else’s,” says educationist Harvinder Kaur, ‘but very persistent questions wanted answers. Questions considering the mystery of life, of mind, which seemed more real to me than a career. Since then I have been on the path. I am prompted by an inner urge, an intense quest, and when I follow it, it leads me to places within myself that I did not know existed. I think awareness is what the process hinges upon.”

“I love thinking,” says internationally renowned cartoonist and radiologist, Hemant Morparia. “I like to rotate the world in my head. I move around holding a mirror to my psyche.”

“It all starts with the rhetorical question, ‘Who am I?’ This question itself takes one through the entire gamut of understanding the self as ego; the self as a truncated fragment – a random particle; then the self as the co-creator and ultimately, the enquiry comes full-circle to the Self not as a part of the whole but as the whole – the ‘one’,” says writer and trainer, Neelam Mehta.

They may have different ways of expressing it, but these seekers are describing the path of jnana yoga.

What is jnana yoga?

All of us embark on the quest of the Self by a path that is most suited to our temperament. Love and devotion towards God is natural to some. Those whose hearts are filled with devotion and overflow with love follow bhakti yoga. Action-oriented souls who believe in doing things and serving society are on the path of karma yoga. A few are more inclined towards austere practices of yoga, meditation and pranayama and lead a life of severe discipline – they are followers of raja yoga.

The intellectually endowed among us would love to believe, but we need to understand before we do. Those among us who question and probe and seek answers to satisfy the intellect first, are on the path of jnana yoga.

Jnana yoga is the path of intelligent inquiry. Like a child who is fascinated by all that he sees and feels, a jnana yogi is interested in the workings of the mind, senses and the universe. He uses his natural curiosity, critical thinking and analytical skills to understand the real nature of himself, the world and its phenomena. He does this externally at first, and then turns the searchlight inwards and starts detached observation of his thoughts, speech and action.

Central to the jnana yogi’s quest is to discover his real self. Who is he? In the course of this search he systematically peels away the layers of body, mind and ego-driven identities surrounding him and ultimately arrives at the pure essence of himself, the soul. Neti, neti (Not this, not this) is his war cry as he ongoingly goes beyond, until he finally rests in the dissolution of his egoic self and discovers that he is nothing other than the All. “Aham brahmasmi,” uttered Adi Shankaracharya in the utter wonder of that discovery. “I am God.”

It is this discovery that is the core of the jnana path. There is nothing but God. There never was. There never will be. The world that we live in and that which comes alive to us through our senses, is, in the ultimate analysis, illusory. And that is because it is impermanent, a play of the Lord who resides in every atom of his creation.

A couple of centuries ago, mankind believed that the earth was flat and it went round the sun, until Galileo came along and told us otherwise.

Now we ‘believe’ that the sun ‘rises’ in the east and ‘sets’ in the west, and experience day and night according to its movements. But we know perfectly well that the sun neither rises nor sets nor travels.

While dreaming, we experience all emotions. We even sweat with fear and have shortness of breath, but breathe easily when we wake up.

We see our reflection in the mirror, but do not mistake the image for our real self.

These are examples of illusion which we easily come out of because we can comprehend the truth behind them. Similarly the world too is an illusion. We can come out of this illusion too, if we wake up to a higher state of consciousness, to a higher reality.

“Brahman satyam, jagat mithyam,” stated Adi Shankaracharya succinctly when he reached journey’s end. This discovery that God is all is crystallised into a philosophy called Advaita (non-dualism).

The jnani’s path is paradoxical – he uses the mind to go beyond the mind. His movement, most often, is fuelled by insights or ideas. A spiritual truth surfaces from within or through a wisdom source, and if he were to spend sufficient time thinking and meditating about it or even simply allowing it to work within him, in time he will be afforded one more insight. Even as one insight gives way to another, the seeker shifts and changes from within, for each insight has the capacity to completely shift the perspective with which oneself, others and life are viewed.

For instance, an insight on the futility of expectation both from oneself and others can shift his relationship with himself and others and help him craft more space within himself for both.

It is the jnani’s capacity to dwell persistently on a question or an insight until it yields an inner shift that enables him to authentically move forward. For there is always the danger of self-deception.

Says Sunita Kashyap, a Mumbai-based writer: “I know of several Vedantins who are so conceited about being on the path of the intellect that they don’t seem to recognise what an ego trap they have fallen into.”

Modern masters

Although the word jnana is derived from the Hindu tradition, the path of the intellect is a familiar one in wisdom traditions such as Buddhism with its insight meditation. As it happens, jnana yoga is ideal for modern times. Our times have favoured the mind. The path for the modern thinker has to include the mind – blind belief is not an option.

Little wonder then that foreigners flock into India chasing Advaita gurus such Ramesh Balsekar, Vimala Thakkar and others. Many teachers of our times like J Krishnamurti, UG Krishnamurti, Eckhart Tolle, Byron Katie and others have all favoured the jnana path.

|

There are many approaches that these teachers have taken to enable us to come to grips with the truth. J Krishnamurti and Eckhart Tolle favour the approach of beginning at the end. Krishnamurti exhorted his followers to practice what he called choiceless awareness – a state where one is effortlessly aware of all that passes through the mind field without censorship. In other words, a state of perfect equanimity free from craving and aversion.

Tolle favours being in the present moment and offers many techniques to experience this, if only momentarily. Both their attempts are to give us a glimpse of the enlightened state, after which we could safely be relied on to strive to make it permanent.

Byron Katie talks of loving what is and offers four questions and a turnaround to all the thoughts that cause us to suffer. The questions: Is this true? Can you absolutely know this to be true? How do you feel when you believe this to be true? Who would you be without this thought? And then a turnaround which means reversing the thought. If the thought is “My husband does not appreciate me”, then the turnaround would be “My husband does appreciate me”. One needs to get at least three examples of this. Another would be, “I don’t appreciate myself.” A third would be “I don’t appreciate my husband.” Says Katie, “As I began living my turnarounds, I noticed that I was everything I called you. In the moment I see you as selfish, I am selfish (deciding how you should be). In the moment I see you as unkind, I am unkind. If I believe you should stop waging war, I am waging war on you in my mind.”

Ramesh Balsekar, on the other hand, encouraged his followers to recognise that God ran the show. Therefore no matter what they did or did not do, there was no cause for guilt or vanity – a sort of escalator ride to surrender.

Krishnamurti and Balsekar were vehemently against techniques of any nature, suggesting that any attempt to change yourself actually took you away from the quest. All you had to do was be with who you are.

The traditional way

In this, they are echoed by the traditionally Indian jnana yoga approach delineated in the Gita,and the Vedas. In thousands of ways the scriptures exhort us to recognise that we are already That which we seek. Therefore, the process was one of eliminating what we are not rather than accumulating fresh layers of personality on our already burdened Self.

The Gita’s message of action in inaction and non-doership is quintessential jnana yoga. In verse after verse of its 18 chapters, Krishna breaks down the ignorance that clouds Arjuna’s indecision, his attachment to his people, his sense of ‘doership’, and shows him the immortality of the soul and oneness of the universe.

The Gita’s heroes, the Pandavas, symbolise the powers of discrimination that one has to awaken with God’s grace, in order to overcome the wild, uncontrolled sway of the senses symbolised by the Kauravas.

The Vedas too offer proof after proof of the essential oneness of creation and the divinity of the Self. Each of the four Vedas – Rig, Yajur, Sama and Atharva – have a profound statement called a mahavakya which indicates ultimate reality that is revealed to a seeker upon enlightenment. Prajnanam Brahma (Consciousness is Brahman) says Rig Veda Aham Brahmasmi (I am Brahman) says Yajur Veda Tat Tvam Asi (Thou Art That) says Sama Veda Ayam Atma Brahma (This Self is Brahman) says Atharva Veda Deep contemplation on even one of the mahavakyas can become the pursuit of a lifetime. Single-minded introspection on the mahavakyas purifies the mind, provides extraordinary insights and leads one to transcendental states of awareness.

The Upanishads

Perhaps nowhere is the truth of life, self and God expressed with as much thrilling clarity and certainty as in the Upanishads, those fabulous snapshots of reality traditionally placed at the end of each of the Vedas. Hence they were also referred to as Vedanta (end of the Vedas). More than 200 Upanishads are known, while just a dozen are considered most important. Of these some of the Upanishads directly discuss the nature of the Self and its relationship with Brahman.

• In Kathopanishad, the technique of knowing the Self is revealed by Lord Yama or the king of Death.

• The Kenopanishad explains the nature of God paradoxically, by contemplating on ‘by whom’ one can see, hear and speak and not ‘what’ one speaks, hears or sees.

• The Mandukya Upanishad reveals the secrets of meditating on the beeja mantra OM, and takes one to the transcendental state of awareness.

• The Mandukopanishad makes a distinction between two kinds of knowledge – para vidya, or the knowledge that leads to Self-realisation, and apara vidya, knowledge of the material world.

• The Chandogya Upanishad establishes the relationship between atman (individual consciousness) and Brahman (Universal consciousness).

• The Taittiriya Upanishad is one of the most important and primary Upanishad, very special to jnana yoga as it sets forth the doctrine of the five kosas or sheaths that conceal the true Self.

Studying, assimilating and contemplating on the teachings of the Vedas and Upanishads is the traditional path of jnana yoga.

All these teachings are encapsulated in two Biblical statements: ‘I am that I AM’ and ‘Be still and know that I am God’.

‘Who am I?’

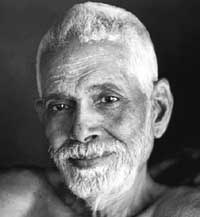

It was 1896. A young lad of 16 was sitting alone in his house in Madurai, when suddenly the fear of death violently overtook him. The shock of this fear left him paralysed. He strongly felt he should solve the problem there and then, and find out what death was like. He decided to dramatise the event and lay still like a corpse. He held his breath and closed his lips tightly so that no sound could escape. “Am I dead?” he asked himself – and the answer was ‘no’. He felt that even though the body was inert, he could still feel the full force of his personality. And a thought came to him in a brilliant flash: “I am not the body, I can hear the voice of ‘I’ within me,” he discovered. “I am the deathless spirit!” The lad’s fear of death vanished once and for all. His ego was lost in the flood of Self-awareness.

Harvinder Kaur Harvinder Kaur‘At 16, I thought my life would be like anyone else’s, but very persistent questions wanted answers.’ |

This lad went on to become one of the most revered spiritual masters of all time – Ramana Maharshi. His famous query ‘Who Am I’ forms the basis of jnana yoga as taught by him. The ‘I’ thought, says Sri Ramana, which makes oneself identify with the body, can be destroyed by depriving it of all thoughts and perceptions that lead to it. Holding on to the ‘I’-thought, that is, the inner feeling of ‘I’ or ‘I am’ and excluding all other thoughts, one constantly questions ‘Who am I?’ or ‘Where does this “I” come from?’ If one can train attention on this inner feeling of ‘I’ and exclude all other thoughts, then the ‘I’-thought will start to subside, he says.

Other great advaita (a non-dualistic teaching which asserts that there is no second, all is only God) gurus include the matchless Nisargadatta Maharaj, an humble paan and cigarette seller in Mumbai, who realised himself three years after his guru told him that he was God. Countless seekers from all over the world sought him out in his tiny attic in central Mumbai to dialogue with him. The book that emerged from these dialogues is considered to be the acme of jnana yoga: I am that.

The practice of jnana yoga

That we live in an illusory world can be easily proven. “I don’t believe this!” we have often exclaimed when we see or receive news that is contrary to our expectations. And this is literally true. “The eyes and ears faithfully send factual messages to the brain, but our mind rejects it because ‘it cannot believe’,” says Uday Acharya, a Vedanta teacher from Mumbai. He cites the following story to illustrate the same:

Bharchu was a minister who was loved by the king for his wit and wisdom. One day, Bharchu made fun of the king and incurred his wrath. The king ordered Bharchu to be executed, but he himself went into mourning, contemplating his hasty and drastic deed. After a year, when the king was still depressed and mourning, his councilors decided to cheer the king and organised a royal hunt in the forest. The king set off for the forest, and passing one of the dwellings, he was shocked to see Bharchu alive and well. Believing Bharchu to be dead, the king mistook him to be a ghost. With great difficulty the foresters convinced the king that Bharchu was not a ghost. The king checked with the executioner who confessed that he had allowed the minister to escape from prison and gave the king evidence to the contrary.

Why did the king see a ghost instead of Bharchu? Was it the fault of his eyes, or was it because he firmly believed that Bharchu was dead? His eyes revealed the existence of Bharchu faithfully. But the mind rejected what the eyes evidenced.

Similarly, the scriptures reveal the truth directly by saying ‘You are That’. Why then, do we not believe in the simple truth? Because of our conditioning; through the process of living untold lives we have accumulated several objections and preconceived notions about who we are that make us unable to take this statement at face value. Low self-esteem, undesirable habits and thoughts, all shroud the truth from us. Hence jnana yoga involves reflection and questioning until the layers of ‘ajnana’ are peeled away and the truth becomes crystal clear.

How can this happen? One cannot claim to have mastered cooking merely by memorising the recipe book. The Mundaka Upanishad says that reading texts and listening to explanations exposes one only to ‘apara’ jnana, which is useless like unedible paddy with its husk intact. Thus the seeker has to make serious and sincere efforts to master and implement these concepts. All masters advocate the cultivation of awareness as a first step. It is the light of awareness that will burn away our illusions and illumine our true Self.

Walking the path

What are some of the stations the seeker passes through on his way to the truth? In the pursuit of this yoga, the seeker experiences, in stages, equanimity, dispassion, detachment, selfless action, renunciation, contemplation on the true nature of the Self, and finally divine grace. Although traditionally self-esteem is nowhere mentioned (perhaps because the traditional seeker was already a person of sound self-worth unlike in our neurotic times) this is undoubtedly a stage we need to pass through before we can shed the ego. Only a healthy ego will enable us to shed it, else insecurity and uncertainty will cause us to cling to this false self.

Hemant Morparia Hemant Morparia‘I like to rotate the world in my head. I move around holding a mirror to my psyche.’ |

Taking responsibility for our thoughts, words, deeds and lives is an important way station. As long as we blame life and others for the way we think and behave, we can never cut through the illusion that others have control over us. Once we recognise that no matter what others or life does, our stuff (thoughts, word, actions) are our own, we take an important step in freeing ourselves from external control and getting anchored from within.

An essential step on the path is the awakening of the intellect. As emotional reactions diminish in intensity and frequency, we arrive at conclusions which are rational and balanced. When someone offends us, we no longer automatically veer towards revenge. We understand the impulse that came over them and we consciously craft a response that can heal the other and the relationship. J Krishnamurti always said that the capacity to not be hurt was the sign of the awakened mind.

Acceptance, the capacity to be with things as they are and not twist them around to suit our needs is an indication that we have neared our zone. We increasingly shift from resistance. Overcrowded buses and trains do not trouble us, nor the fact that we are late for an important appointment. Even major disappointments and losses, such as unrequited love, or losing a job cannot shake our equanimity because we are in touch with reality. We recognise that we cannot control the other’s action and if the other does not love us, so be it. The job may be gone, but if that is what is, why mourn for it? Why not instead focus on making this an opportunity for good? At this stage we are in control over our minds and can volitionally turn off the faucet of unwholesome thoughts and feelings and redirect them into nourishing and productive avenues.

Ramana Maharshi Ramana Maharshi‘I am not the body, I can hear the voice of ‘I’ within me. I am the deathless spirit.’ |

The penultimate stage is surrender. Here we actively recognise that our lives are being lived for us and that our egoistic interference is only messing up the sublime design that is being crafted for us by the Higher Power of which we are a part. Trustingly, we let go and allow the Higher Impulse to flow unresistingly through us. ”Deeds are done, but there is no doer thereof,” said the Buddha. This is surrender, non-doership. Actions flow through us, but they are not dictated by egoistic needs, but rather emerge through a spontaneous response to the present moment.

Methodology

In his treatise on jnana yoga, Vivekachudamani, Adi Sankara describes eight steps to Self-realisation. The first seven steps describe the efforts the seeker has to put in which will lead him to the last stage, samadhi. The steps involve:

1. Viveka: Developing the ability to discriminate between knowledge and ignorance, the real and unreal, the perishable and the imperishable.

2. Vairagya: To develop indifference ordispassion for material and sense attachments and attractions

3. Shat- sampatti or six virtues

Sama: Calmness of mind

Dama: Restraint of senses

Uparati: Withdrawal of the senses

Titiksha: Tolerance and endurance

Shraddha: Faith in the guru and the scriptures

Samadhana : One-pointed concentration

4. Mumukshutva : Developing an intense longing for liberation

5. Shravana : Receiving jnana from a realised master

6. Manana : Assimilating this knowledge through constant contemplation

7. Nididhyasana : Practical application of this knowledge, along with meditation and other spiritual disciplines until the seeker becomes that knowledge

8. Samadhi : A state of deep meditation that takes one to Self-realistion

Meditation is an integral part of jana yoga. In fact, the word ‘jnana’ is used interchangeably with ‘upasana’ (meditation) in the Upanishads, says Uday Acharya. The Kathopanishad speaks of OM as an object of meditation and also as the subject of Self-kowledge. Upasana is meditation involving concentration, steadiness, and contemplative thought. It involves mental disciplines that are helpful for learning, retaining, and contemplating on Self-knowledge.

Swami Sivananda, spiritual master and founder of the Divine Life Society, also gives practical tips to set one on the quest of this truth by these methods:

• Meditation on the all-pervading air, ether, light, expansive sky, expansive ocean.

• Meditation on abstract virtues like mercy, generosity, magnanimity, courage, patience, peace, balance, poise.

• Meditation on abstract concepts, like:

– Names and forms do not exist; the world is a dream; nothing belongs to me

– The whole world is my body; the whole world is my home

– I suffer and enjoy in all bodies; I work through all hands; I eat through all tongues; I see through all eyes; I hear through all ears

– All is good; all is sacred; all is one; All is God (Brahman); All bodies are mine. I am the Immortal Self in all.

Grace

For any spiritual pursuit to become yoga, divine grace is absolutely necessary, say the scriptures.

This is because a jnani will be unable to cross the final stage on his own on the strength of his knowledge and spiritual practice because of maya, says Veda Vyasa in the Bhagawatam. He says that the few yogis who reach the final stage of yoga begin to believe that they have crossed the ocean of illusion completely, and that itself is an illusion. “A yogi must know that the ocean of maya can be crossed with the grace of Krishna,” says Vyasa.

Only grace can tip you over from your own limited self into the vast expansion of cosmic consciousness.

All yogas lead to jnana

Karma and bhakti too are accessories to jnana. A karma yogi and bhakti yogi both develop an attitude of surrender, devotion and love. Their selfless sadhana leads to purity of thought, mind and speech, and they automatically become eligible for acquiring and assimilating jnana. Jnana yoga, therefore, is the culmination of a life committed to learning, combined with spiritual practices that include karma, bhakti, tapas, ethical values and grace.

Said Vivekananda, “Seek the Highest, always the Highest, for in the Highest is eternal bliss. If I am to hunt, I will hunt the lion. If I am to rob, I will rob the treasury of the king. Seek the Highest.”

So seek jnana, for there can be nothing higher than jnana, as a verse from the Vishnu Purana says: Jnanameva Para Brahma(Jnana is Brahman), jnanam bandhaya kalpate (the bonding is because of jnana), jnaanathmakamidam vishwam (the entire universe is an illustration of jnana), na jnaanadvidyathe param (there is nothing other than jnana)!

To read more such articles on personal growth, inspirations and positivity, subscribe to our digital magazine at subscribe here

Life Positive follows a stringent review publishing mechanism. Every review received undergoes -

- 1. A mobile number and email ID verification check

- 2. Analysis by our seeker happiness team to double check for authenticity

- 3. Cross-checking, if required, by speaking to the seeker posting the review

Only after we're satisfied about the authenticity of a review is it allowed to go live on our website

Our award winning customer care team is available from 9 a.m to 9 p.m everyday

The Life Positive seal of trust implies:-

-

Standards guarantee:

All our healers and therapists undergo training and/or certification from authorized bodies before becoming professionals. They have a minimum professional experience of one year

-

Genuineness guarantee:

All our healers and therapists are genuinely passionate about doing service. They do their very best to help seekers (patients) live better lives.

-

Payment security:

All payments made to our healers are secure up to the point wherein if any session is paid for, it will be honoured dutifully and delivered promptly

-

Anonymity guarantee:

Every seekers (patients) details will always remain 100% confidential and will never be disclosed